How Uzbekistan Can Escape the Middle-Income Trap (Volume 20, Issue 2)

A Tashkent metro station. Source: Viola Fur

Home to three in four humans, middle-income countries often struggle to grow further and reach high-income status. To escape this trap, Uzbekistan, as a lower-middle income country, should consider policy recommendations in three sectors: enterprise, talent and energy.

By Viola Fur

Three in four people live in middle-income countries—and risk remaining stuck at that level of development. Over the past few decades, many countries have successfully navigated the transition from low- to middle-income status, but then struggled to grow further and ultimately achieve high-income status. This phenomenon, to which the over 100 middle-income countries are susceptible, is known as the "middle-income trap." The 2024 World Development Report (WDR) outlines a framework for escaping the middle-income trap, based on which this paper suggests policy recommendations for three policy areas: enterprise, talent, and energy.

Uzbekistan, the most populous country in Central Asia, and a lower-middle-income country in early 2025, aims to achieve upper-middle-income status by 2030 and to grow further thereafter. This objective was formally codified in 2023, and has been a key pillar of government policy since. Its push towards an upgrade in income status mirrors those of other middle-income countries, such as Thailand and Nigeria; its challenges and opportunities in striving for growth may be instructive to all.

Striving for growth

Uzbekistan achieved independence in 1991, ushering in growth rates of 5 percent or more under Islam Karimov’s presidency from 1991 to 2016. [1] He pursued a state-dominated approach to economic growth. During the 1990s, Uzbekistan’s economy grew thanks to economic diversification, as the country began to industrialize and decrease its dependency on the import of energy and foodstuffs. [2] From 2004 to 2016, annual growth rates averaged around 8 percent thanks to investments in capital-intensive primary goods, and the favorable conditions faced by Uzbek exports under a global commodity price boom. [3] Yet there were also signs of economic strain. The central bank closely managed the exchange rate, rendering the Uzbek soum increasingly overvalued with a substantial premium between the official and the parallel market rate. Cotton, one of Uzbekistan’s biggest exports, had been sold at low prices due in part to underpaid, forced labor by millions, including children, which eventually gave rise to an international boycott campaign from around 2010 to 2022. Uzbekistan began to struggle to maintain isolationist trade policies, from high import tariffs to restricting formal export ability to a handful of firms, in an increasingly interconnected world.

After Karimov’s death in 2016, his successor, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, embarked on a series of economic reforms. He liberalized the currency policy to a managed float, which ended the inefficient, informal currency exchange practices of his predecessor; reduced customs duties on thousands of goods; and allowed agricultural businesses beyond just the monopolist Uzagroexport to export their products. [4] Since then, other reforms have included the slow but promising privatization of certain state-owned enterprises (SOEs), a marked effort to join the World Trade Organization by 2026, and a curtailing of petty corruption. Uzbekistan’s current aim, codified in the Uzbekistan 2030 Strategy, is achieving upper-middle-income country status by 2030. [5] Its numerical objectives are a GDP per capita of US$4,000, with a gross GDP target of US$16 billion.

The middle-income trap

Classical economic theory has dictated that economic convergence between nations will allow lower-income countries to “catch up” to higher-income ones, but this is not always borne out in practice. Solow’s growth model suggests that the returns to capital are higher in lower-income countries which are not yet at their “steady state,” so capital should flow to these countries, allowing them to grow faster than their higher-income counterparts. There has been some limited empirical evidence in favor of this theory. For instance, growth rates in developing countries were on average 2.5 percentage points higher than in advanced economies between 1990 and 2007. [6] However, while increased investment can help low-income countries grow, after a certain level of development, capital inflows, by themselves, become insufficient as engines of growth. Indeed, by the mid-2010s, growth rates decelerated in middle-income countries. Driving this are stagnating total factor productivity (TFP) rates—a measure of efficiency, or the ability to generate economic output from given inputs—which does not increase with investment flows after a certain level of development. [7]

The “middle-income trap” is a phenomenon whereby countries successfully achieve middle-income status, but then struggle to grow further and become high-income countries, remaining “trapped” at middle-income levels. The term has only become more relevant over time, as middle-income countries have grown in number and share of the global population. Diverse middle-income countries from Mexico and Montenegro to Egypt and Vietnam have struggled to reach high-income status for decades. [8] Further, due to rising protectionism, geopolitical tensions, and rising debt-servicing costs, escaping the middle-income trap is only becoming more challenging.

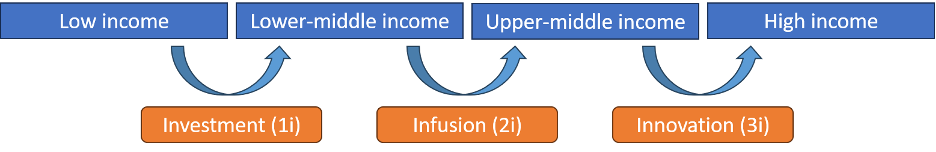

The 2024 WDR argues that to escape this trap, middle-income countries need to move sequentially from prioritizing investment to infusion, and from infusion to innovation. This is referred to as the 3i strategy. 1i refers to investment—increasing expenditure in education, healthcare and other growth-boosting fields—which low-income countries should prioritize. Then, at the 2i level (investment plus infusion), lower-middle-income countries should emulate and implement technologies and ways of operating from other countries. Finally, upper-middle-income countries should leverage that infusion to innovate and add value to global value chains (3i, or investment, infusion plus innovation). [9] The experiences of many Eastern European countries, which grew from lower-middle-income to high-income status in around two decades, illustrate how, among others, accession to the EU incentivised the infusion of new technologies, after which the countries began to innovate and add new forms of value to global supply chains. Other countries which successfully escaped the middle-income trap—and did so without leveraging oil reserves—include Uruguay and Singapore.

Figure 1 - Pathways to economic growth, adapted from the 2024 World Development Report

Policy recommendations

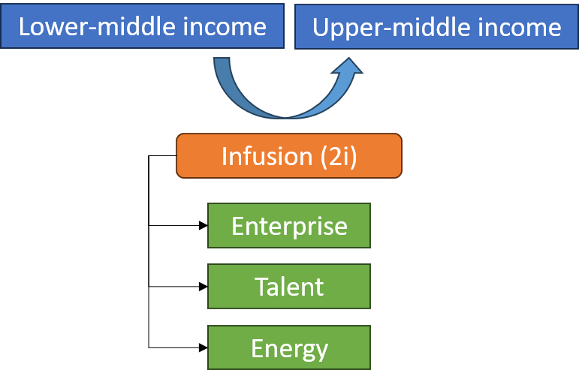

As Uzbekistan is a lower-middle-income country striving to reach upper-middle-income status, it is currently at the 2i level, and should focus on investment and infusion. Infusion-promoting policy recommendations break down into three categories, per the WDR: enterprise, talent and energy. This is illustrated on Figure 2.

Figure 2 - Components of infusion, adapted from the 2024 World Development Report

Enterprise

Despite substantial progress, government spending remains the primary engine of growth in Uzbekistan. In 2022, government spending, including by SOEs, made up over 40 percent of GDP, well above average compared to other middle-income countries. [10] Government-directed lending is still common, with state-owned banks lending disproportionately to SOEs. [11] SOEs also benefit from tax and regulatory exemptions which are not enjoyed by the broader private sector, nor are they always transparently communicated. Combined, these factors conceal market incentives, crowd out the private sector, strain fiscal sustainability, and hinder growth.

Uzbekistan should build on past accomplishments to increase the pace of SOE reform. In early 2021, the Strategy for SOE Reform for 2021–2025 set as an objective a reduction in the number of SOEs by 75 percent. [12] In February 2024, the Law on privatization of State Property was signed, clarifying the mechanics of privatization and designating the State Asset Management Agency to lead the privatization of state property. [13] Additionally, a few high-profile privatizations have already taken place, such as that of Ipoteka, one of the largest five banks. The privatization of two others is underway, albeit slowly. Other forms of preferential treatment are being removed as a part of accession negotiations for the WTO. These policies have allowed for the beneficial infusion of foreign technologies and best practices.

To continue promoting infusion in terms of enterprise, Uzbekistan’s SOE reforms should accelerate. Prioritization may be beneficial: privatizations could focus on key industries which would benefit the most from increased competition, and in which significant efficiency gains can be expected. Additionally, the rollback of SOE subsidies and exemptions should continue. As of 2023, around 900 SOEs benefited from tax and duty subsidies; this number should decrease to levels conducive to fair competition and economic growth. [14] Finally, transparency is paramount. Where there is a genuine economic rationale for the preferential treatment of SOEs, the corresponding information should be made publicly available. To track progress made towards the Strategy for SOE Reform for 2021–2025 and other such laws, data should also be available on the number of SOEs and the progression of privatization projects. In this way, the economic gains from enterprise can be maximized.

Eastern European countries’ experiences may prove instructive, as they too had market-dominating, often inefficient, SOEs for historical reasons. Slovakia, for instance, was a lower-middle-income country in 1992, yet a combination of SOE privatization and EU accession, both conducive to the infusion of new technologies, pushed the country to upper-middle-income and eventually high-income status by 1996 and 2007, respectively.

Talent

Uzbekistan’s talent-related challenges centre on poor labor allocation across sectors and slow productivity growth within certain sectors. Around the world, countries often fall into the middle-income trap due to slowdowns in TFP growth; Uzbekistan may have the same experience. [15] Economic growth has primarily come from capital accumulation and labor productivity increases in the industrial sector, while productivity gains in agriculture and services have been far more modest. Yet precisely these sectors employ most of the population, at a combined 77 percent as of 2023, with employment in the agricultural sector remaining stubbornly high compared to countries at similar levels of development. [16] Moreover, despite increasing employment rates, output per worker in the services sector is over 40 percent below the average among lower-middle-income countries. Productivity in the agricultural sector also remains low relative to comparator countries. [17] Uzbekistan is fortunate to have a young and growing population, projected to reach approximately 50 million by 2050, but they will struggle to translate this asset into economic growth if the highest value-add sectors employ such a small sliver of the population while the majority employers contribute proportionately little to GDP.

Uzbekistan should promote structural transformation through enhanced labor mobility across sectors, and enable productivity growth in lagging sectors. First, to support labor reallocation across sectors, the public sector should enable alternative employment pathways, notably in the private sector, for those leaving the agricultural sector. Some labor mobility frictions have decreased in recent years, such as the abolishment of the propiska system, which controlled internal migration and even travel within Uzbekistan. Yet more could be done to ease access to non-agricultural employment pathways, particularly in the fast-growing services sector, which exhibits lower barriers to entry than industry. Crucial to this pivot is the ability of a competitive private sector to create jobs at a pace which matches the growing population and urbanization. Second, to support productivity increases within sectors, Uzbekistan should leverage infusion to increase the productivity of those working in the agriculture and services sector, to mirror the productivity increases in the industrial sector. This can be done by gradually exposing these sectors to domestic and foreign competition.

Other countries should carefully observe Uzbekistan’s attempts to improve both across-sector structural transformation and within-sector productivity increases. It will not be easy to accomplish both. Over the past few decades, growth in Sub-Saharan Africa has been driven by across-sector labor reallocation while productivity within sectors has remained stagnant; meanwhile, Latin America has had the opposite experience, with impressive within-sector productivity increases but only muted structural transformation across sectors. [18] Yet there have also been some success stories, notably in Southeast Asia. Thailand, for instance, was propelled from lower-middle- to upper-middle-income status in recent decades by both across-sector labor reallocation, with workers formerly employed in agriculture finding work in the manufacturing and especially the service sector; and by within-sector productivity increases as the development of the industrial and services sectors has deepened. [19] Uzbekistan can both learn from these experiences, and be instructive in its own right, as it leverages infusion in terms of both labor reallocation and productivity increases.

Energy

The energy sector accounts for over 75 percent of Uzbekistan’s greenhouse gas emissions, indicating that infusion in this sector could benefit not just economic growth rates, but also environmental sustainability. [20] Encouraging energy sector reforms are currently underway, namely infusing market norms into a historically closed sector by phasing out regressive energy subsidies, but must be complemented by other policies to ensure equity and long-term sustainability. Uzbekistan announced in 2023 that energy subsidies, in place since the USSR, would be phased out by 2030. [21] The policy change was driven in part by a sensible desire for fiscal consolidation, especially after the mild but marked spike in the general government debt-to-GDP ratio, from 17 percent in 2017 to 31 percent in 2022. It also reverses what had been a regressive subsidy, with wealthier households who consume more energy receiving proportionately more funds than lower-income households. Yet given the inefficiencies in energy use due to outdated infrastructure, passing on full energy prices to businesses and consumers may challenge the sustainability of the policy given the lack of formal compensatory mechanisms, such as cash transfers for low-income households, which are widely implemented following subsidy reforms worldwide. [22] Moreover, the environmental strains exerted by energy consumption continue to be felt, regardless of who is paying. To complement the subsidy removal, Uzbekistan should improve both existing infrastructure and the regulatory environment governing future energy infrastructures.

To improve existing infrastructure, Uzbekistan should leverage the infusion of energy efficiency–boosting technologies, and foster regional energy integration. Energy efficiency rates have historically been low in Uzbekistan. Despite gradual improvements since 2000, energy intensity rates, as of 2022, were still above the global average of 1.3 at 1.5 kWh per dollar. Building construction norms, in which proper insulation or passive heating and cooling technologies have historically not been prioritized, are partly at fault for this. Yet fostering partnerships with foreign firms, which do have expertise in such construction techniques, can encourage the infusion of best practices and thus improve energy efficiency rates. Additionally, for better regional integration, the power grids of Central Asian countries should be more interconnected. The Central Asian Power System (CAPS) has historically connected the region’s power grids, but significant parts of this system were discontinued after the countries gained independence. Yet not only is regional energy integration sound policy—while Uzbekistan produced much of the electricity in CAPS, even they imported electricity during peak demand periods—it is also an avenue towards the infusion of technologies and best practices from countries in the region. [23] Uzbekistan should support efforts to restore CAPS in full, as well as explore avenues to energy integration beyond Central Asia, for instance through the potential power grid cable under the Caspian Sea that would connect Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan with Azerbaijan.

Infusion should also be leveraged to make future infrastructures energy efficient, especially as significant migration to urban areas is forecast. To this end, the International Energy Agency has called for the expansion of minimum energy performance standards (MEPS). This regulatory instrument is presently in force for appliances and equipment, ensuring that they meet certain energy standards, but its coverage could be expanded to encompass products in other sectors, such as housing and transportation. [24] Moreover, injecting competitiveness into key sectors, including the energy sector, via SOE reform could lead to marked productivity gains by allowing for the infusion of new ideas and technologies into a historically static sector. Through these policies, future energy infrastructure can be more sustainable and efficient, and thereby conducive to growth.

Argentina’s energy policies may be exemplary for Uzbekistan. The country began phasing out energy subsidies gradually in 2016, replacing it with a “social tariff” to provide targeted support to low-income households. [25] Capitalizing on the fiscal savings and through international partnerships, Argentina then leveraged infusion to improve the energy efficiency of existing infrastructure, as well as adopting MEPS.

Conclusion

Facing up to the middle-income trap is crucial to economic growth for the majority of the global population who live in middle-income countries, and who risk remaining trapped at that level of development. Having grown from low-income to lower-middle-income status through investment (1i), they now face the more challenging tasks of reaching upper-middle-income status through infusion (2i) and high-income status through innovation (3i) per the 2024 World Development Report. These transitions have never been easy, and are now harder than ever. Trade protectionism, which threatens to exclude emerging economies from established global supply chains, is on the rise among high-income countries, and the environmental burden of unsustainable growth is more evident than ever. Yet just as many countries have remained in the middle-income trap for decades, so too have some—Slovakia, South Korea, Uruguay—successfully escaped the trap and reached high-income status.

Uzbekistan, as a lower-middle-income country, should focus on the infusion (2i) of new technologies to reach upper-middle-income status. Infusion should be implemented across three areas: enterprise, talent, and energy. In terms of enterprise, SOE reform should accelerate, removing unnecessary and non-transparent privileges which inhibit the efficiency gains from competition. Privatization in key sectors should also accelerate. Gains from talent could come from the promotion of labor reallocation across sectors, particularly away from agriculture, as well as from productivity increases within lagging sectors, namely agriculture and services. Energy reform should leverage infusion to improve current infrastructures’ energy efficiency and regional integration, and to promote the adoption of regulatory best practices. These three pillars should propel Uzbekistan towards its target of upper-middle-income status by 2030.

Citizens of middle-income countries will be watching Uzbekistan’s upcoming policies. Uzbekistan’s SOE reforms will be instructive not just to its neighbors but to all middle-income countries where SOEs occupy a large role, from Egypt and Georgia to Vietnam and Pakistan. Structural transformation across sectors has stumped many countries in Latin America while intra-sector productivity increases have been muted in several Sub-Saharan African countries; if Uzbekistan succeeds in these areas, they will have much to teach. Energy subsidy reforms underway in Ecuador and Nigeria reflect Uzbekistan’s experiences, while increased energy efficiency and integration are top of mind for policymakers worldwide. With less than half a decade until the 2030 deadline, Uzbekistan’s policies may have global reverberations.

About the author

Viola Fur is a macroeconomist and policy advisor with 5+ years of experience. Viola is currently a 2024 - 26 ODI Fellow and Economist at the Ministry of Economy and Finance of Uzbekistan. Viola holds a Master in Public Policy from Yale University and First Class Honours degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics from the University of Oxford.

Endnotes

Kobil Ruziev, “Uzbekistan’s Development Experiment: An Assessment of Karimov’s Economic Legacy,” Europe‑Asia Studies 73, no. 7 (May 19, 2021): 1303, https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2021.1919602.

Jeromin Zettelmeyer, “The Uzbek Growth Puzzle,” IMF Staff Papers 46, no. 3 (1999): 274.

Kobil Ruziev, “Uzbekistan’s Development Experiment: An Assessment of Karimov’s Economic Legacy,” Europe‑Asia Studies 73, no. 7 (May 19, 2021): 1310, https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2021.1919602.

Mamuka Tsereteli, “The Economic Modernization of Uzbekistan,” essay in Uzbekistan’s New Face (Washington, D.C.: American Foreign Policy Council, 2018), 90.

World Bank Group, World Development Report 2024: The Middle‑Income Trap, July 22, 2024, 5, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-2078-6.

Kemal Dervis, “The Future of Economic Convergence,” Brookings, February 13, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-future-of-economic-convergence/.

Patrick Imam and Jonathan Temple, “At the Threshold: The Increasing Relevance of the Middle‑Income Trap,” IMF Working Papers 2024, no. 091 (April 2024): 8, https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400274855.001.

World Bank Group, World Development Report 2024: The Middle‑Income Trap, July 22, 2024, 2, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-2078-6.

World Bank Group, World Development Report 2024: The Middle‑Income Trap, July 22, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-2078-6.

The World Bank, “Uzbekistan Public Expenditure Review, December 2022: Better Value for Money in Human Capital and Water Infrastructure,” World Bank, Washington, D.C., December 2022, 12–13, https://doi.org/10.1596/39518.

World Bank Group, Toward a Prosperous and Inclusive Future: The Second Systematic Country Diagnostic for Uzbekistan (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, April 18, 2022), 10.

“State‑Owned Enterprises Reform Strategy Approved,” Uzbekistan State Asset Management Agency, March 30, 2021.

“The Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan ‘On Privatization of State Property’ Was Adopted,” Agency for Management of State Assets of the Republic of Uzbekistan, February 15, 2024.

Aziza Umarova, “Challenges to Democratic Market Reforms in Uzbekistan and the Risks of State Capture from State‑Owned Enterprises,” Center for International Private Enterprise, May 17, 2023.

Shekhar S. Aiyar et al., “Growth Slowdowns and the Middle‑Income Trap,” IMF Working Papers 13, no. 71 (March 2013): 7, https://doi.org/10.5089/9781484330647.001.

World Bank Group, Toward a Prosperous and Inclusive Future: The Second Systematic Country Diagnostic for Uzbekistan (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, April 18, 2022), 18.

World Bank Group, Toward a Prosperous and Inclusive Future: The Second Systematic Country Diagnostic for Uzbekistan (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, April 18, 2022), 18.

Xinshen Diao, Margaret McMillan, and Dani Rodrik, “The Recent Growth Boom in Developing Economies: A Structural Change Perspective,” NBER Working Paper no. 23132 (February 2017), 2, https://doi.org/10.3386/w23132.

Peter Warr and Waleerat Suphannachart, “Benign Growth: Structural Transformation and Inclusive Growth in Thailand,” in The Developer’s Dilemma (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 98, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192855299.003.0005.

World Bank Group, Toward a Prosperous and Inclusive Future: The Second Systematic Country Diagnostic for Uzbekistan (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, April 18, 2022), 14.

Fitch Wire, “Progress on Some Uzbekistan Reforms Ahead of Scheduled Energy Tariff Increase,” Fitch Ratings, December 19, 2023.

Anit Mukherjee et al., “Cash Transfers in the Context of Energy Subsidy Reform: Insights from Recent Experience,” World Bank Group, June 30, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1596/39948.

Farkhod Aminjonov, “Central Asian Countries’ Power Systems Are Now Isolated, but Not Everyone Is Happy!*,” Eurasian Research Institute, 2016.

International Energy Agency, Uzbekistan 2022 Energy Policy Review, October 4, 2022, 16, https://doi.org/10.1787/be7a357c-en.

Fernando Giuliano et al., “Distributional Effects of Reducing Energy Subsidies: Evidence from Recent Policy Reform in Argentina,” Energy Economics 92 (October 2020): 3, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2020.104980.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect the opinions of the editors or the journal.