Macro-Fiscal Impact and Governance Dynamics in Ecuador’s Debt-for-Nature Swaps (Volume 21, Issue 1)

Ibero-American Ministerial Conference on Environment and Climate Change in the Galapagos Islands. Source: Public Domain

By Shreya Bajaj and Amit Sheoran

Introduction

Countries today face twin and interconnected challenges: reducing the sharp rise in debt-to-GDP ratios that followed the COVID-19 pandemic, and creating fiscal space for climate and nature-related investments consistent with the Paris Agreement. Although the global debt-to-GDP ratio declined in 2024 from its post-pandemic peak, it remains above 2019 levels. [1] At the same time, meeting the financing needs of climate action requires an estimated USD 5 trillion annually until 2030, with developing economies alone requiring approximately USD 2.4 trillion each year. [2] These fiscal and environmental pressures underscore the need for innovative mechanisms that simultaneously support climate adaptation and mitigation while easing debt burdens, particularly in developing countries.

Among such instruments, debt-for-nature swaps (DFNS) have re-emerged as a policy tool capable of alleviating sovereign debt distress while mobilizing resources for environmental conservation. Ecuador’s Galápagos Bond (2023) and Amazon Biocorridor Program (2024) represent recent large-scale and headline examples of this approach. However, beneath their conservation narrative lie complex fiscal and governance trade-offs. [3]

This paper examines the Galápagos Bond (hereafter, the Blue Bond) as a case study. Its scale, innovative financial architecture, and explicit linkage between debt relief and marine conservation make it a salient example for evaluating the effectiveness of DFNS in aligning fiscal sustainability with environmental objectives. The analysis assesses the extent to which Ecuador’s swap has achieved its dual aims of debt relief and conservation financing, arguing that while some progress has been made, fiscal gains remain limited, transaction and administrative costs have been substantial, and sovereign discretion in managing both debt and natural resources has been constrained. The evidence suggests that, at least in this instance, comparing the direct costs DFNS represents a high-cost and institutionally intrusive alternative to a hypothetical standard restructuring.

Limited Debt Relief

At first glance, the Blue Bond appears to have provided moderate debt relief. The operation was carried out through a special purpose vehicle (SPV), which allowed the government to repurchase USD 1.6 billion of its debt at an average price of 40 cents on the dollar. To finance this buyback, the SPV issued a USD 656 million bond linked to marine conservation and lent the proceeds to the government. Because the debt was repurchased at a discount, reflecting distressed bond prices due to default risk, and the new bonds carried lower coupon rates backed by guarantees from the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Ecuador achieved net present value savings of approximately USD 843.5 million, corresponding to a 2.16% reduction in total external debt. [4]

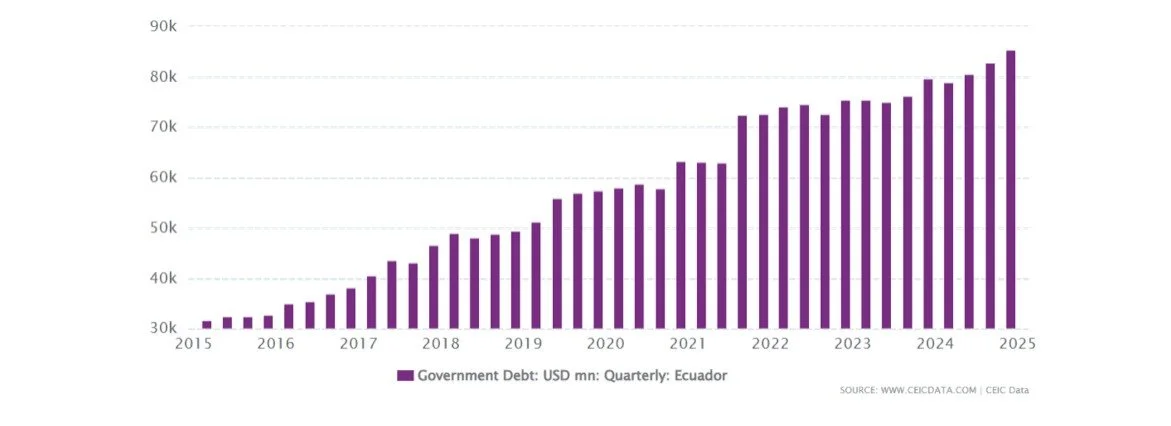

While significant in absolute amount, compared to overall debt levels, the percentage reduction in overall debt remains minuscule. Functionally, the transaction is closer to a liability management operation: it lowers interest costs and extends maturities on a narrow subset of external bonds, rather than substantially altering the level and composition of Ecuador’s overall public debt. [5] Consequently, Ecuador remains responsible for servicing most of the debt over an extended horizon, with only modest additional fiscal space for social or developmental spending. Further, the DFNS does not address Ecuador’s underlying fiscal or structural vulnerabilities that have contributed to its long-term debt unsustainability. [6]

From a creditworthiness standpoint, such discounted buybacks of the targeted sovereign bonds, when detached from structural reform or fiscal consolidation, can be perceived unfavorably by credit rating agencies. [7] Ecuador's sovereign rating remains at “B-”, reflecting persistent concerns about debt sustainability and limited investor confidence. [8]

Figure: Ecuador's National Government Debt from Dec 2015 to Dec 2024 (Quarterly) (in million U.S. dollars)

Environmental Impact

While the Galápagos Blue Bond generates fiscal savings earmarked for conservation, these savings are limited in magnitude (approximately USD 323 million) [9] and dispersed over an extended time horizon (approximately 18.5 years), limiting the scope of activities that can be meaningfully financed. The annualized nature of funding flows, spread across nearly two decades, constrains project design, privileging continuity over scale and leaving limited flexibility for large-scale, capital-intensive environmental programs. This forces the government to focus on small-scale projects rather than transformative initiatives that align with Ecuador’s broader development and climate priorities.

Another critical policy question concerns whether these funds represent additional environmental financing or merely substitute for existing public expenditure. Academic and policy debates increasingly highlight that, in fiscally constrained countries such as Ecuador’s, DFNS funds often replace rather than supplement domestic conservation spending. [10] Given that the government already bears statutory responsibilities for fisheries management, biodiversity protection, and stewardship of protected areas, the resources channeled through the swap may simply relabel pre-existing expenditures rather than expand the overall conservation budget. In that case, the operation primarily “ring-fences” a portion of debt-service savings to conservation, while the remaining fiscal space generated can be redeployed to other government priorities, rather than increasing the overall fiscal resources directed toward conservation efforts. [11]

High Transaction, Insurance, and Governance Costs

The headline figures of nominal debt relief in Ecuador’s debt-for-nature swap obscure a complex cost structure that significantly diminishes the country’s net financial gains. Multiple layers of transactional, insurance, and governance costs absorb a substantial portion of the resources freed for conservation or fiscal space.

In Ecuador’s case, the DFC provided USD 656 million in political risk insurance to underwrite the Blue Bond. [12] While this mechanism enhanced investor confidence and enabled the issuance of the bond at lower yields, it also imposed substantial annual premium payments on Ecuador. Similarly, the IDB extended an USD 85 million guarantee, subject to fees and contractual conditions that further constrained Ecuador’s financial discretion. [13] These arrangements, while protecting creditors from default risk, shift the fiscal burden to the debtor, embedding hidden costs that reduce the swap’s effective value.

Beyond sovereign guarantees, the transaction’s financial architecture involved over eleven private insurers, with sizable underwriting and administrative fees paid to banks like Credit Suisse that arrange the transactions. [14] These entities earned relatively high fees as a share of the bond’s total issuance value. The cumulative cost of these services inflates the swap’s expense structure and channels a meaningful share of the nominal “debt savings” to private actors rather than to the debtor state or conservation outcomes.

In addition to financial intermediation costs, governance and administrative expenses associated with the conservation trust fund further erode the net benefit. The Galápagos Life Fund (GLF) is an independent conservation trust created under the swap to receive and allocate the earmarked conservation flows and manage the endowment; it is governed by a multi-stakeholder board including government officials and representatives of international NGOs and conservation organizations, and its operation entails recurring operational, monitoring, and oversight costs. [15]

To put the scale in perspective, investors in the Blue Bond receive a coupon payment of 5.645%. When the insurance premium is added, the effective rate increases to 6.975%. After accounting for all additional financing costs, including guarantee and management fees, the total effective coupon rate rises to 7.387%. [16] As a result, these multi-layered transaction costs diminish Ecuador’s effective fiscal gains from the Blue Bond.

Degradation of National Sovereignty

Ecuador’s debt-for-nature swaps illustrate a deeper tension between innovative financial design and the preservation of national sovereignty. By structuring conservation financing through SPVs and foreign-registered private trusts, these arrangements outsource control over natural resource governance to entities that operate beyond the reach of domestic democratic institutions. This institutional design, while presented as a safeguard for fiduciary transparency, raises questions about accountability, autonomy, and the locus of decision-making authority in environmental governance. [17]

In Ecuador’s case, the GLF is registered in The United States, rather than within Ecuador’s jurisdiction. [18] Formally, its eleven-member board comprises five representatives of the Ecuadorian government and six non-government members. [19] Civil society critics argue that key non-government seats and officer roles are occupied by international NGOs, philanthropic organizations, and conservation-finance intermediaries, giving foreign actors a structurally influential position and leaving the Ecuadorian state in a minority within the fund’s governing body. [20]

This institutional configuration transfers strategic authority over conservation priorities, project approvals, and resource allocation to external actors. As a result, critical ecological assets, such as the Galápagos Marine Reserve, are managed under governance structures detached from national and community oversight. Donors and investors justify such arrangements as mechanisms to ensure fiduciary discipline and reduce political risk. However, they also reproduce global asymmetries of power and embed the logic of financial conditionality within environmental governance. [21]

The implications extend beyond administrative control. Once established, these governance frameworks cannot be unilaterally altered by Ecuadorian authorities; conservation funds cannot be reallocated, and contractual terms are legally binding under foreign jurisdiction. This constrains national policy discretion, particularly in fiscal and environmental domains, and limits the ability of elected governments to realign conservation strategies with evolving social or developmental priorities.

Critics contend that such arrangements entrench a form of environmental neo-colonialism, in which debtor countries become “renters” or “managers” of their own natural assets under the supervision of external financial and conservation institutions. [22] These actors, motivated by risk mitigation and investor confidence, inevitably shape priorities toward asset preservation and financial performance, often at the expense of local socio-economic needs. Moreover, the legally binding environmental conditionalities attached to these swaps may constrain Ecuador’s ability to negotiate future fiscal policies or debt instruments flexibly, reinforcing long-term dependence on externally mediated financial mechanisms.

In essence, the Ecuadorian experience demonstrates how DFNS, while innovative in form, can reconfigure sovereignty itself, substituting national control for externally enforced environmental governance. This raises pressing questions about whether such instruments advance sustainable development or simply repackage dependency through green financialization.

Comparison with Traditional Debt Restructuring

Ecuador’s DFNS was executed at a time when the country faced a high external debt burden and lacked affordable access to international capital markets. Having already restructured its commercial debt in 2020, Ecuador sought an alternative mechanism that could provide fiscal relief without the negative market signaling and investor uncertainty typically associated with another restructuring. The Blue Bond offered a way to refinance part of its external debt.

Empirical research suggests that DFNS are ill-suited for periods of acute debt distress, as their limited scope and transaction size prevent them from meaningfully restoring debt sustainability. [23] The Ecuadorian case reinforces this assessment: the magnitude of fiscal relief achieved through the Blue Bond was negligible relative to the country’s total debt stock, yielding approximately a 2% reduction in Net Present Value (NPV) of debt levels compared to the 21% average reduction in external debt levels typically obtained in post-COVID sovereign restructurings. [24]

In addition to their limited quantitative impact, DFNS are significantly more expensive from a fiscal and administrative perspective. Traditional debt restructurings, whether through negotiated haircuts or maturity extensions, avoid the multi-layered insurance, guarantee, and intermediation fees embedded within DFNS structures.

Moreover, although traditional restructurings often come with IMF programmes that set hard fiscal targets and therefore limit the overall budget, they usually do not give external actors direct control over individual spending decisions. Once the deficit and debt path is agreed with the IMF, it is still the government that decides how to use any fiscal space created by debt relief, how much to put into health, education, infrastructure or debt reduction, within the broad constraints of the programme and domestic politics, rather than an external board managing a separate, earmarked pool of resources. While both instruments involve intricate negotiations and case-specific design features, recent initiatives to improve coordination among Paris Club creditors and emerging lenders such as China have sought to strengthen the predictability of traditional restructuring mechanisms, even if progress remains uneven and contested. Against this backdrop, DFNS often appear as financially inferior substitutes, delivering limited macro-fiscal gains at relatively high transaction and governance cost. In principle, a more conventional restructuring of Ecuador’s external debt could have addressed solvency concerns more directly and at lower cost for a given amount of debt relief, even if it would have entailed higher short-term investor uncertainty.

Recommendations for Future DFNS

Ecuador’s experience underscores the need to reform the design and governance of future DFNS to ensure that they deliver genuine fiscal and environmental benefits without undermining national autonomy. Key recommendations include the following:

Streamline Legal and Financial Structuring: Current DFNS deals are highly customized, which makes them slow and expensive to put together. Building on emerging toolkits, governments and multilaterals should move toward a small set of semi-standard templates for swap contracts, guarantees, and conservation trust funds to cut advisory costs, shorten negotiations, and embed basic transparency and participation safeguards.

Introduce Performance-Based Coverage Incentives: Performance-based insurance premiums can better align incentives between debtor countries and guarantors. Under this approach, premiums would decrease as debtor governments meet agreed targets related to transparency, disclosure, and environmental outcomes.

Rebalance Governance to Protect Sovereignty and Inclusion: Future DFNS should combine accountability with domestic ownership. Boards overseeing conservation funds should allocate equal representation to government agencies, local authorities, and Indigenous communities.

Institutionalize Public Reporting and Participatory Oversight: Mandatory public disclosure and stakeholder consultation mechanisms should be embedded in all DFNS frameworks. This includes civil society-led audits, participatory impact assessments, and independent review panels to evaluate fund performance. These measures would improve transparency while strengthening community engagement in conservation management. [25]

Enhance Transparency Through Digital Platforms: Establishing open-access online platforms publishing comprehensive information on fund budgets, grant allocations, project performance indicators, and governance meeting minutes can significantly improve accountability. This would enable external scrutiny by citizens, researchers, and oversight bodies, thereby reinforcing institutional legitimacy and reducing opportunities for opacity or misuse. [26]

Linking the swaps with adaptation outcomes: Adaptation activity is GDP-conserving in the long term. It allows the economy to withstand adverse climate events and avoid future damages. This bolsters the country's expected future GDP. DFNS, though historically focused on conservation, has huge potential to support and enhance financing for adaptation activities, thereby enhancing resilience and reducing the debt burden in the future.

Opportunities for developed countries to fulfill their historical responsibilities: The ongoing climate change can be attributed to the existing stock of greenhouse gases. Evidence shows that it is the developed countries that have contributed disproportionately to this stock and are thereby mandated to provide and mobilize resources for climate actions of developing countries (Article 9 of the Paris Agreement). Debt swaps with significant NPV benefits and climate action funding are a promising way for developed countries to fulfill these mandates.

Conclusion

Ecuador’s experience with DFNS reveals a paradox at the intersection of fiscal policy, environmental governance, and national sovereignty. While these instruments successfully mobilize much needed conservation finance and offer marginal improvements in debt servicing capacity, their macroeconomic and institutional implications are far more complex. The Ecuadorian case demonstrates that the fiscal benefits of swaps are limited in scale, eroded by high transaction and insurance costs, and accompanied by a gradual cession of sovereign authority over the governance of natural resources.

The dominance of international NGOs, financial institutions, and external trustees within the governance architecture exemplifies the risk of transforming states into “renters” rather than stewards of their ecological assets.

To move forward, the design of DFNS must evolve toward models that preserve fiscal sovereignty while maintaining transparency and credibility. Governance frameworks should embed domestic ownership, inclusive representation, and community participation as central pillars, rather than peripheral considerations. Achieving this balance is essential not only for Ecuador but for the broader legitimacy, scalability, and developmental relevance of DFNS in addressing global challenges at the intersection of finance, climate, and sovereignty.

About the authors

Shreya Bajaj is pursuing Master of Public Policy at Yale University, and Amit Sheoran is pursuing Master of International Policy at Stanford University.

Endnotes

[1] “General Government Gross Debt,” International Monetary Fund, n.d., https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/GGXWDG_NGDP@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD.

[2] “Finance and Investment for Climate Goals,” OECD, n.d., https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/finance-and-investment-for-climate-goals.html.

[3] “To Protect Galápagos Islands, Ecuador Turns to Innovative Financing,” A Fact Sheet From the Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy Project, May 2023, https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2023/09/to_protect_galapagos_ecuador_turns_to_innovative_funding.pdf; Adam Tomášek,“Debt for Nature Coalition,” Debt for Nature Coalition, October 5, 2025, https://www.debtfornature.org/case-studies-blog/amazon.

[4] World Economic Forum, “This is Ecuador’s historic debt-for-nature deal,” June 9, 2023, accessed October 21, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/06/ecuadors-historic-debt-for-nature-deal/; Tess Woolfenden, “Debt-for-nature Swaps Reduce Debt Seven Times Less Than Debt Restructurings,” Debt Justice, May 29, 2025, https://debtjustice.org.uk/press-release/debt-for-nature-swaps-reduce-debt-seven-times-less-than-debt-restructurings.

[5] IDB, “Ecuador Completes World’s Largest Debt-for-Nature Conversion With IDB and DFC Support,” n.d., https://www.iadb.org/en/news/ecuador-completes-worlds-largest-debt-nature-conversion-idb-and-dfc-support.

[6] Aruna Chandrasekhar and Yanine Quiroz, “Q&A: Can Debt-for-nature ‘Swaps’ Help Tackle Biodiversity Loss and Climate Change?” Carbon Brief, July 16, 2024, https://www.carbonbrief.org/qa-can-debt-for-nature-swaps-help-tackle-biodiversity-loss-and-climate-change/.

[7] Martin Kessler, “Debt-to-Sustainability Swaps (D2S): A Practical Framework,” FinDevLab, April 21, 2025, https://findevlab.org/debt-to-sustainability-swaps-d2s-a-practical-framework/.

[8] “Ecuador ‘B-’ Ratings Affirmed On Debt-For-Nature Swap; Outlook Remains Negative,” S&P Global, December 9, 2024, accessed October 21, 2025, https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/regulatory/article/-/view/type/HTML/id/3297194.

[9] DB, “Ecuador Completes World’s Largest Debt-for-Nature Conversion.”

[10] Andre Standing, “Galapagos Debt-swap: ‘These Deals Are Being Used to Privatize the Management of Strategic Areas Without the Consent of Those Who Inhabit These Territories’,” Coalition for Fair Fisheries Arrangements, June 9, 2025., https://www.cffacape.org/publications-blog/galapagos-debt-swap-these-deals-are-being-used-to-privatize-the-management-of-strategic-areas-without-the-consent-of-those-who-inhabit-these-territories.

[11] Ibid

[12] DFC, “Financial Close Reached in Largest Debt Conversion for Marine Conservation to Protect the Galápagos,” May 9, 2023, https://www.dfc.gov/media/press-releases/financial-close-reached-largest-debt-conversion-marine-conservation-protect.

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid

[15] GLF, “Home - GLF,” November 9, 2025, https://galapagoslifefund.org.ec/?utm.

[16] Sophia Green, “Innovative Financing Tool Helps Protect Galápagos Islands,” Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy, February 11, 2025, https://www.pew-bertarelli-ocean-legacy.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2024/12/innovative-financing-tool-helps-protect-galapagos-islands.

[17] Maria Luisa Gambale, “Debt-for-Nature Swaps Are Failing the Global South - PassBlue,” PassBlue, August 8, 2024, https://passblue.com/2024/08/05/debt-for-nature-swaps-are-failing-to-end-global-souths-money-woes/.

[18] Gambale, “Debt-for-Nature Swaps Are Failing the Global South.”

[19] DFC, “Financial Close Reached in Largest Debt Conversion.”

[20] Standing, “Galápagos Debt-Swap.”

[21] Sarah Glendon, “Ecuador’s $650 Million Debt-for-nature Swap Targets Galápagos Protection,” Columbia Threadneedle, n.d.; https://www.columbiathreadneedle.com/en/gb/intermediary/insights/ecuadors-650-million-debt-for-nature-swap-targets-galapagos-protection/.

[24] Latindadd, “Summary of the Debt-swap for Nature in the Galapagos Islands,” August 21, 2025, https://latindadd.org/informes/summary-of-the-debt-swap-for-natur-in-the-galapagos-islands/; Standing, “Galápagos Debt-Swap.”.

[22] Pablo Laixhay and Maxime Perriot, “Debt-for-nature swaps 2.0, a deceptive solution,” Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt, n.d., https://www.cadtm.org/Debt-for-nature-swaps-2-0-a-deceptive-solution.

[23] Dennis Essers, Danny Cassimon, and Martin Prowse, “Debt-for-climate swaps: Killing two birds with one stone?” Global Environmental Change, November 2021; Marcos Chamon, Erik Klok, Vimal V Thakoor, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer, “Debt-for-Climate Swaps: Analysis, Design, and Implementation,” International Monetary Fund, August 12, 2022, https://www.imf.org/en/publications/wp/issues/2022/08/11/debt-for-climate-swaps-analysis-design-and-implementation-522184.

[24] Debt Justice, “Debt-for-nature Swaps Reduce Debt Seven Times Less Than Debt Restructurings,” May 29, 2025,https://debtjustice.org.uk/press-release/debt-for-nature-swaps-reduce-debt-seven-times-less-than-debt-restructurings.

[25] Standing, “Galápagos Debt-Swap.”

[26] Marc Jones, “Record Galapagos debt-for-nature swap scrutinized over transparency irregularities claims,” Reuters, September 27, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/record-galapagos-debt-for-nature-swap-scrutinized-over-transparency-2024-09-27/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect the opinions of the editors or the journal.