Navigating the Climate-Conflict-Migration Nexus in Sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from South Sudan (Volume 21, Issue 1)

Floods create fresh catastrophe for South Sudan on its difficult journey from war to peace. Source: United Nations Mission in South Sudan

By James Maker Atem

Executive Summary

Three interconnected crises—violent conflict, forced migration, and climate change—are changing Sub-Saharan Africa's population and natural environments. South Sudan, one of the most vulnerable countries in the region, is a paradigmatic example of how climatic stresses fuel already-existing sociopolitical conflicts while also disrupting livelihoods and displacing large numbers of people. Using detailed insights from South Sudan, this report examines the interconnected dynamics of the conflict, migration, and climate nexus, offering guidance for programmatic and integrated policy responses in similarly-affected situations. This report aims to understand better how climate change affects migratory patterns and intensifies violence by using an interdisciplinary approach combining political philosophy, migration studies, and climate science. The paper argues that climate is exacerbating local conflict by heightening resource scarcity/extremes and worsening migration push factors. Drawing on the present state of South Sudan, the author provides some suggestions on lessons and best practices. The findings are meant to underscore the necessity of integrated policy recommendations addressing resource-based conflict prevention, climate resilience, and sustainable migration management to strengthen regional stability.

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa is increasingly a global hotspot where the overlapping effects of violent conflict, mass migration, and climate change threaten sustainable development and human security. Decades of civil conflict, weak institutions, and recurrent climate shocks have created a complex situation in South Sudan, one of the most affected countries in the region, that defies simple remedies. This report aims to explain the closely linked events of what has come to be recognized as the climate-conflict-migration nexus in South Sudan. While climate change contributes to displacement through more frequent and more extreme weather events that uproot communities, its broader impact—when viewed through layers of political exclusion, socioeconomic vulnerability, and historical grievances—also amplifies current dangers and creates new kinds of insecurity. [1]

Designing policies that go beyond isolated treatment and toward coordinated, anticipatory response requires understanding these intricate links. In doing so, this report adds to the growing body of literature aiming to identify the challenges at the intersection of climate, conflict, and migration and chart a path toward peace, resilience, and inclusive development under compounding crises.

The Impacts of Climate Change

In 2020, over one million people were displaced in South Sudan due to climate-induced events. [2] Piguet and Laczko argue that this situation leaves communities vulnerable to hunger and further displacement, compounded by poor farming practices and inadequate investment in climate-resilient agriculture. [3] Furthermore, Lidigu argues that through deforestation and land degradation, climate change contributes to the loss of biodiversity, aggravating environmental vulnerabilities. [4] However, greater coordination between humanitarian agencies and national authorities could address implementation gaps in adaptation measures.

The Climate-Conflict Nexus

A number of sources establish the causal links between climate stressors and increased conflict. Abel et al. argue that climate variability often manifests through floods and droughts, which in turn amplify struggles over scarce resources such as water and grazing land. [5] These environmental stressors intensify conflicts between pastoralist and farming communities.

Shifts in rainfall are one particularly potent climate stressor. Coumou and Robinson show how declining rainfall patterns as well as prolonged droughts disrupt water availability, thereby aggravating competition among communities. [6] Additionally, Schilling et al. show how erratic rainfall patterns reduce the availability of grazing areas, thus leading to violent clashes. [7] Tiitmamer asserts that agricultural productivity is severely impacted by extreme weather, creating a cascade of socioeconomic stressors that intensify violent conflicts—as we see in South Sudan. [8] Notably, unpredictable flooding further compounds water management challenges, generating a threat of resource scarcity. Finally, the cyclical and repeated nature of these extreme weather patterns can reinforce conflict.

The Role of Governance

Similarly, poor governance worsens outcomes and reduces the effectiveness of climate and conflict interventions. Benjaminsen et al. caution against oversimplifying the nexus between climate change and violent conflicts. [9] While armed conflicts are significant, conflict intersects with environmental stressors to augment displacement trends in South Sudan. Additionally, it is important to consider other underlying drivers of violent conflict, such as historical grievances and failures of governance. For a fragile state like South Sudan, Ahmed and Hipp argue that governance institutions often lack the capacity and legitimacy to address complex challenges such as resource-related conflicts. [10] Building on this, Murtaza and Rahman show that governance in post-conflict settings is characterized by inefficiencies and corruption, as well as limited accountability. [11] Finally, Okeke observes that the struggle for good governance is eclipsed by an absence of inclusive decision-making processes. [12]

The effects of climate change are also mediated through governance mechanisms. Hendrix and Salehyan show how dwindling natural resources, worsened by climate variability, increase existing vulnerabilities. [13] This, in turn, creates conditions that fuel conflicts. Furthermore, endemic governance failures undermine the effectiveness of climate adaptation policies. Baalen and Mobjörk contend that climate change acts as a threat multiplier, and its impact on conflict is mediated through other elements such as governance capacity and social resilience. [14] Additionally, Raleigh and Urdal demonstrate that water scarcity is mediated through governance structures. [15] In this way, efficacious management of shared water resources can mitigate tensions.

Case Study: South Sudan

Across the Sahel, incidence of climate-related conflicts and displacement of people in vulnerable regions increasingly pose significant challenges to socioeconomic and political livelihoods. [16] Meanwhile, climate change aggravates resource scarcity in areas with pre-existing instabilities, such as South Sudan. [17] Here, prolonged droughts and flooding have disrupted agriculture and pastoralism, thus contributing to ethnic tensions and livelihood loss. [18]

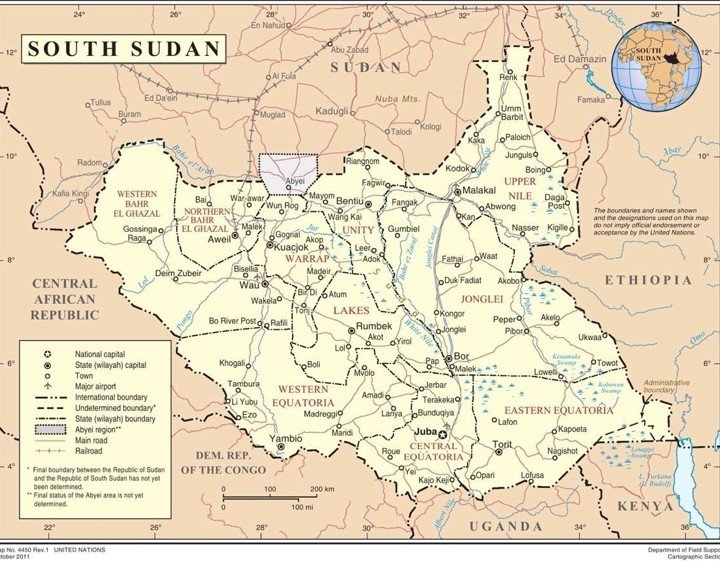

Figure 1: Map of South Sudan. Source: United Nations

Contextualization

Local Conflict and Violent Outbreaks

From the early 1900s until today, South Sudan has long experienced intercommunal violence, particularly between the Dinka, Murle, and Nuer communities—groups that are often described in the literature as ethnolinguistic communities rather than strictly ethnic or linguistic groups. Much of this is retaliatory in nature, as displaced livestock keepers from Jonglei State and host communities in Magwi County, Eastern Equatoria, have engaged in a deadly cycle of revenge killings. [19] Aside from migration-related violence, other causes of conflict include territorial disputes, politically motivated violence, and ethnic clashes. In Western Equatoria State, the Azande and Balanda populations have had violent clashes since 2015, driven largely by climate-induced pressures such as declining agricultural productivity, erratic rainfall, and competition over shrinking fertile land and forest resources. [20] Intercommunal violence is also occurring in Tonj Counties of Warrap State, particularly Tonj East communities, including Luachjang, Jalwau, and Akok, where cattle raiding and revenge killings are rampant. [21] In Jonglei State, fishermen of the Twic East and Duk communities clashed in June 2025 over the ownership of Biothagany, a small island in the Sudd swamp. [22] Lastly, in Nassir County of Upper Nile State, recurrent outbreaks of politically motivated violence among the Naath (Nuer) youth have been partly attributed to the combined effects of climate change, including recurrent flooding, loss of grazing land, and competition over dwindling natural resources. [23]

Displacement within South Sudan

Conflict, resource competition, and displacement depend on several factors, such as dynamics of conflicts, level of vulnerability, and response or adaptation capacity. Van Baalen & Mobjork argue that resource-dependent populations are forced to migrate to resource-rich areas, while Peters et al. observe that climate-related environmental change induces short-distance migration, which is cyclical and seasonal. [24] Abel et al. note that the decline in rainfall in the north of South Sudan has pushed nomadic groups to move further south, increasing competition for scarce resources and exacerbating intergroup violence. [25] This instability forces many residents to flee their homes to seek safety elsewhere, causing population pressure in neighboring states and instigating a vicious cycle of conflict related to territory and land management. A 2023 report from the World Bank shows how the increasing frequency of climate events exacerbates the already-dire conditions in displacement camps, where access to and utilization of basic resources also remains limited. [26] The same report predicts that climate-related shocks could displace an additional 86 million people across Sub-Saharan Africa by 2050, with South Sudan among the hardest hit.

Figure 2: Residents of Mading-Bor, Jonglei State, moving to safer grounds after Nile River burst its banks. Source: UNMISS, 2024.

Climate Impacts

Over the past twenty years, climate variation in the region has increased, manifesting as prolonged droughts, erratic rainfall, desertification, and increasingly severe flood events. Especially in farming and pastoralist communities, these changes have placed significant pressure on already-stressed natural resources, fueling local competition over land, water, and pasture. [27]

Figure 3: A village in Bentiu, Unity State, submerged in floodwater following a devastating overflow. Source: Human Rights Watch, 2025.

Methodology and Sampling

The study engaged 95 survey respondents drawn from flood-affected areas across South Sudan, including Jonglei State (Bor, Twic East, Duk, and Pigi Counties), Unity State (Bentiu), Upper Nile State (Malakal), Central Equatoria State (Juba), Eastern Equatoria State (Magwi County), Western Equatoria State (Yambio County), and Warrap State (Twic County). These regions were purposely selected because they represent the intersection of prolonged flooding, local resource competition, and displacement. Respondents included community leaders, humanitarian practitioners, local government officials, researchers, peacebuilding facilitators, and displaced persons, reflecting a cross-section of actors directly engaged in or affected by the climate-conflict-migration dynamics.

Given the study’s focus on South Sudan’s most affected flood-prone and conflict-affected regions, respondents were selected based on their institutional role, geographic exposure to climatic shocks, and involvement in peacebuilding or humanitarian response. This was then supplemented by snowball sampling, allowing key informants to recommend other knowledgeable participants within their professional or community networks. This approach ensured both regional diversity and depth of contextual understanding, while recognizing that reliance on referrals could risk some degree of homogeneity in perspectives.

Resource-Based Conflicts

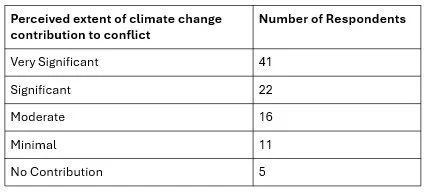

To assess the interplay of climate stressors, weak governance, and resource competition, the study asked survey respondents to what extent climate contributes to local conflicts. Out of 95 respondents, 41 (43.16 percent) indicated that climate change contributed very significantly to local conflicts, 22 (23.16 percent) significantly, 16 (16.84 percent) moderately, 11 (11.58 percent) minimally, and 5 (5.26 percent) no contribution. Qualitative interview data further revealed that prolonged droughts and recurrent flooding are perceived to disrupt traditional livelihoods, exacerbating tensions among pastoralist and farming communities. The results are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1: Extent of climate change contribution to local conflicts in South Sudan

The responses reveal a strong majority in agreement of the role climate change plays in exacerbating local conflicts. One policymaker, with visibility into nationally-aggregated data, in Juba stated:

Climate change is a catalyst to the already worse situation. It adds fuel to the fire. The conflicts that have occurred before and the ones occurring now are worse because people are fighting over land and water.

When resources are made scarce—land for grazing or agriculture, potable water for drinking or cattle—competition over those resources increases, raising the threat of conflict. In fact, this competition often escalates into intercommunal conflicts between the ethnic groups such as Nuer and Dinka.

The findings also reveal that ethnic rifts aggravate these tensions, with some respondents blaming historical grievances. According to a local leader from Twic East in Jonglei State:

The rains come suddenly and take away everything, leaving the community with nothing. During the dry season, the conditions become unbearable. It is hard to fight or defend ourselves when we have nothing to eat or drink.

This will to fight—even in the face of deprivation—comes from long-standing tensions between ethnic groups. Defense is made more difficult due to a lack of resources, but this doesn’t noticeably reduce conflict; it simply makes the conflict more grueling for those who wage it.

Resources affected by climate changes

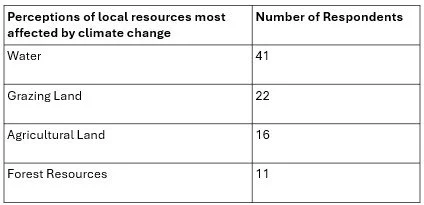

The study sought to identify which natural resources are the most affected in South Sudan. Out of 95 respondents, 63 (66.32 percent) selected water, 17 (17.89 percent) grazing land, 11 (11.58 percent) agricultural land, and only 4 (4.21 percent) forest resources. The results are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2: Perceptions of local agricultural resources most affected by climate change

A clear majority of respondents identified water as the resource most affected by climate change—encompassing needs for livestock, human consumption, and agriculture. Although these uses are interrelated, they often become sources of tension because different groups prioritize them differently: pastoralist communities depend on water for grazing and livestock survival, while farming communities rely on it for crop cultivation. Competition over access to limited, well-watered land thus fuels conflict between the two livelihood systems.

Extent of climate change contribution to displacement

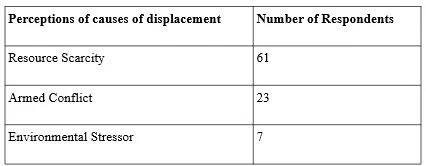

The respondent results suggest that the nexus between protracted conflict and climate variability has contributed to a cycle of displacement in South Sudan. Owing to prolonged civil wars, as well as severe droughts and recurrent floods, livelihoods have been devastated and communities forced to flee their homes. Thus, the study sought to identify the leading causes of displacement. Out of 95 respondents, 61 (64.2 percent) selected resource scarcity, 23 (24.1 percent) armed conflicts, 7 (7.37 percent) environmental stressors, and 4 (4.21 percent) clan feuds. The results are illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3: Perceptions of causes of displacement

Local experts responded that resource scarcity is the most significant driver of displacement. Scarcity, specifically of water and arable land, worsens intercommunal tensions and leads to forced migration. According to one humanitarian worker in Juba:

Villages are submerged when floods come. People are forced to leave and many no longer return because the land is not usable.

According to one respondent from Jonglei State, internal displacement is often cyclical, with communities migrating between flood-prone areas and drought-stricken regions. He observed that:

During droughts, there is fight over water. When it rains, we lose everything to floods. It is a hard time, and we have nowhere to go.

Of course, resource scarcity can also lead to armed conflict, as the literature shows (see above). In this way, each of the causes above can be understood to be primary while also interacting with others, generating the conflict-climate-migration nexus.

National Responses: progress and challenges

South Sudan has implemented some policies aimed at climate adaptation and resource management, such as the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA). However, these efforts are hampered at the local level by endemic political instability and chronic weak governance, in addition to existing resource constraints.

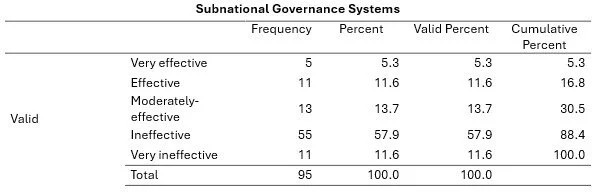

Thus, the study sought to assess whether subnational governance structures—such as county administrations, traditional authorities, and local peace committees—are effective in managing resource-related conflicts. Out of 95 respondents—majority of whom live and work outside the capital, Juba—5 (5.3 percent) selected very effective, 11 (11.6 percent) effective, 13 (13.7 percent) moderately effective, 55 (57.9 percent) ineffective, and 11 (11.6 percent) very ineffective. The results are illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4: Subnational governance structures and Conflict Management Mechanisms

A significant portion of respondents viewed local governance as ineffective in implementing natural resource management and conflict resolution policies, particularly those related to land use, water allocation, and intercommunal peacebuilding. One policymaker in Juba observed:

Most policies exist on paper. Good policies, yet there is lack of funding and capacity to implement them effectively. For instance, the floods and droughts often come faster than our solutions.

Furthermore, existing weak institutional frameworks constrain the state’s ability to effectively address conflict while efforts to manage displacement are similarly constrained. Although South Sudan has adopted the Kampala Convention on Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), implementation has been poor.

Discussion

As local experts, the 95 respondents bring to bear their own experiences and knowledge of climate in conflict in a number of South Sudan’s states. Their responses to this survey indicate that climate contributes significantly to local conflict, water resources are most affected by climate change, resource scarcity is the primary driver of displacement in South Sudan, and local governance is ineffective at addressing resource management and conflict mitigation.

Findings and Policy Recommendations

Extreme weather patterns have led to resource-based intercommunal conflicts in South Sudan, and the efficacy of conflict resolution and climate adaptation efforts has been hampered by weak governance. The connection between droughts, floods, and seasonal migration, as well as how resource scarcity triggered by climate change fuels violent conflict which in turn triggers forced migration, is the primary dynamic in South Sudan. Consequently, effective governance is imperative for breaking the cycle of climate-triggered conflicts and migration. Therefore, national frameworks must prioritize climate resilience and conflict management. Specific actions that can be taken to improve this situation are the following:

Strengthen Local Governance and Conflict Resolution Mechanisms: Enhance the capacity of local authorities to manage displacement, mediate disputes, and coordinate resource-sharing among communities. This approach would empower counties and payams to address land and water conflicts before they escalate into large-scale violence. This can be accomplished through redoubled efforts by the national government, in coordination with international partners and resources.

Invest in Climate-Resilient Infrastructure and Early Warning Systems: Develop infrastructure to support early warning mechanisms, drought-resistant agriculture, and sustainable water storage systems. These initiatives would help reduce the vulnerability of flood- and drought-prone communities while promoting adaptation and long-term peacebuilding. Again, the national government in Juba must assume responsibility for cross-state infrastructure, in partnership with domain experts and civil engineering bodies.

Finally, further research opportunities include evaluating how social and cultural aspects influence reactions to migration brought on by climate change, as well as how South Sudan's migratory patterns are affected by urbanization.

Conclusion

The report concludes that climate change amplifies violent conflicts and displaces communities in South Sudan. Despite national and regional efforts, weak governance structures aggravate these conditions, underscoring the need for integrated solutions. Thus, this report advances our understanding of the interplay among climate, security, and migration by focusing on the context-specific dynamics and the role of governance in militating against climate-triggered crises. The researcher has argued that addressing climate change, violent conflicts, and migration requires a multipronged approach that integrates climate adaptation, conflict prevention, and management of migration patterns and dynamics to implement adaptive and preventive strategies.

About the author

James Maker Atem is a researcher specializing in international law, conflict resolution, and water security in the Nile Basin. James is the managing director of the Climate Justice & Peace Nexus (CJP Nexus), a social enterprise dedicated to expanding solar-powered agro-hubs, sustainable energy access, and climate-resilient livelihoods for displaced and rural communities across East Africa. His work integrates AI-driven climate adaptation tools, green entrepreneurship models, and peacebuilding strategies to strengthen community resilience and advance inclusive development.

Endnotes

[1] Sarah Zingg, “Exploring the Climate Change–Conflict–Mobility Nexus”, Migration Research Series, no. 70 (Geneva: International Organization for Migration, 2021) .

[2] Nicklas Sax et. al., “How does climate exacerbate root causes of conflict in Zambia?” Climate Security Pathway Analysis, October 2023, https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/10748070-6d0c-42d3-ae14-1486fd28d318/content.

[3] Etienne Piguet, Antoine Pécoud, Paul Guchteneire, “Migration and Climate Change: An Overview,” Refugee Survey Quarterly 33(3): 1–23, 2011.

[4] Leon Lidigu, “Why Tanzania, South Sudan are drying up faster than peers,” The EastAfrican, December 10, 2024, https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/sustainability/climate/why-tanzania-south-sudan-are-drying-up-faster-than-peers-4852664

[5] Guy J. Abel, Michael Brottrager, Jesus Crespo Cuaresma, and Raya Muttarak, “Climate, Conflict and Forced Migration,” Global Environmental Change 54: 239–249.

[6] Dim Coumou, and Alexander Robinson, “Historic and Future Increase in the Global Land Area Affected by Monthly Heat Extremes,” Environmental Research Letters 8 (3): 034018.

[7] Janpeter Schilling, “On Rains, Raids and Relations: A Multimethod Approach to Climate Change, Vulnerability, Adaptation and Violent Conflict in Northern Africa and Kenya,”(PhD diss., Universitat Hamburg, 2012).

[8] Nhial Tiitmamer, “South Sudan’s Devastating Floods: Why There Is a Need for Urgent Resilience Measures,” The Sudd Institute, November 23, 2020, https://www.suddinstitute.org/publications/show/5fbcef5b321bd.

[9] Tor A. Benjaminsen, Koffi Alinon, Håvard Buhaug, and Jill T. Buseth, “Does Climate Change Drive Land-Use Conflicts in the Sahel?” Journal of Peace Research 49 (1): 97–111.

[10] Ahmed Kher Mohamud, “Intercommunal Conflict Over Natural Resource: The Case of Northern Kenya,” 1963-2011 (Thesis, University of Nairobi, Kenya, October 2012), http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/11404.

[11] Ashfaq U. Rehman, Asghar Khan, and Shughla Ashfaq, “The Centre-Periphery Relations and Governance Issues: The Role of Decentralisation in Post-Conflict North-Western Pakistan,” Journal of Humanities, Social and Management Sciences (JHSMS) 3, no. 2 (December 2022): 169–81, https://doi.org/10.47264/idea.jhsms/3.2.12.

[12] J. Okeke, “The African Peace and Security Architecture: A Liberal Approach to Peace and Security,” African Security Review, 29 (2020): 19-36.

[13] Cullen S. Hendrix and Idean Salehyan “Climate Change, Rainfall, and Social Conflict in Africa,” Journal of Peace Research 49, Issue 1 (2012): 35–50.

[14] Sebastian Van Baalen and Malin Mobjörk, “Climate Change and Violent Conflict in East Africa: Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Research to Probe the Mechanisms,” International Studies Review 20, Issue 4 (2018): 547–575.

[15] Clionadh Raleigh, “Political Marginalization, Climate Change, and Conflict in African Sahel States,” International Studies Review, 12(1) (March 2010): 69–86.

[16] Joern Birkmann, et. al.,“Framing Vulnerability, Risk and Societal Responses: The MOVE Framework,” Natural Hazards 67 (2013): 193–211;

[17] Sunday Didam Audu, “Freshwater scarcity: A threat to peaceful co-existence between farmers and pastoralists in northern Nigeria”, International Journal of Development and Sustainability, Vol. 3 No. 1 (2014), pp. 242-251.

[18] François Gemenne,“Why the Numbers Don’t Add Up: A Review of Estimates and Predictions of People Displaced by Environmental Changes,” Global Environmental Change 21, supple. 1 (2011): S41–S49.

[19] Kateryna Dyshkantyuk, et. al., “Assessing UN Support for Climate Change Responses in Conflict-Affected States,” (Columbia SIPA Capstone Project, Columbia University, New York, May 2023).

[20] United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS),“Brief on Violence Against Civilians in Tambura, Western Equatoria,” June 2021, https://unmiss.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/quarterly_brief_on_violence_affecting_civilians_april_-_june_2024.pdf.

[21] Radio Tamazuj, “Tonj East: 9 Killed in Communal Clashes,” October 8 2020, https://www.radiotamazuj.org/en/news/article/tonj-east-9-killed-in-communal-clashes.

[22] PaanLuel Wël, “13 People Killed and Over 20 Wounded in Deadly Clashes Between Ayual and Hol Communities in Biothagany, Jonglei,” June 7, 2025, https://paanluelwel.com/2025/06/07/13-people-killed-and-over-20-wounded-in-deadly-clashes-between-ayual-and-hol-communities-in-biothagany-jonglei/.

[23] Nyagoah Tut Pur, “South Sudan Army Attacks Displace Thousands in Nassir,” Human Rights Watch, February 27, 2025, https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/02/27/south-sudan-army-attacks-displace-thousands-nasir.

[24] Sebastian Van Baalen, and Malin Mobjörk,“Climate Change and Violent Conflict in East Africa: Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Research to Probe the Mechanisms,” International Studies Review 20 no. 4 (December 2018) :547–575,

[25] Guy J. Abel, M. Brottrager, J. Crespo Cuaresma, and R. Muttarak, “Climate, Conflict and Forced Migration,” Global Environmental Change 54: 239–249, 2019.

[26] World Bank, “Rainfed Agriculture,” 2015, http://water.worldbank.org/topics/agricultural-water-management/rainfed-agriculture, accessed December 13, 2014 .

[27] Thomas A. Smucker, et all., “Differentiated Livelihoods, Local Institutions, and the Adaptation Imperative: Assessing Climate Change Adaptation Policy in Tanzania,” Geoforum 59 (February 2015): 39–50, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.11.018.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect the opinions of the editors or the journal.