The Nuclear Energy Race: The West's Three-Pillar Failure in Leadership (Volume 21, Issue 1)

Financing Low Carbon Technology, Including Nuclear Energy, at the United Nations Climate Change Conference UNFCCC COP29 held at Baku. Source: International Atomic Energy Agency

By Ibrahim Mustafayev and Orkhan Akbarov

In the global push to create sustainable energy systems, countries face a fundamental challenge: providing reliable, affordable, carbon-free electricity at scale. Solar and wind power have emerged as the titans of clean energy, but their intermittent output requires costly backup systems that remain technologically and economically unproven. Fossil fuels offer reliability but carry mounting environmental and political costs. Caught between intermittent renewables and contentious fossil fuels, many countries are revisiting nuclear power as the only proven pathway to firm, zero-carbon baseload electricity. The global nuclear industry is thriving, with roughly 70 reactors currently under construction worldwide. [1]

However, the nuclear renaissance is unfolding without the West. [2] This divergence matters far beyond electricity generation: nuclear energy underpins energy security, industrial competitiveness, and geopolitical influence. Countries that control nuclear technology command leverage in international markets, shape global safety standards, and secure strategic partnerships with emerging economies seeking reliable baseload power. Yet, the West risks permanent marginalization in this resurgent industry, not due to technological inferiority, but because of structural failures in how it approaches nuclear energy development.

This paper argues that Western nuclear energy lags behind state-backed powers due to three interconnected failures: misguided innovation strategies that prioritize bespoke designs over replication, fragmented financial frameworks that expose vendors to existential risks, and eroded industrial capabilities from decades of sporadic construction. Addressing these structural weaknesses through coordinated policy reforms is essential for the West to reclaim global nuclear leadership and secure its energy future.

The Replication Imperative: Efficient Innovation in Nuclear

The nuclear energy industry is hindered by over-customization in two types of innovation: design and process. Design innovation refers to creating novel reactor architecture and bespoke safety features, while process innovation focuses on improving construction methods, manufacturing techniques, and supply chain coordination. In the past, countries that focused on design innovation have failed to build a robust nuclear energy industry, while countries focused on supporting process innovation have unlocked nuclear energy. Too often, countries in the West have systematically pursued design innovation while neglecting process innovation. This approach has meant that their nuclear energy industry is marked by fragmented markets and multiplied risks for first-of-a-kind (FOAK) nuclear technologies, while failing to drive efficiency and compromising standardization.

To understand why design innovation often backfires, consider the core simplicity underlying nuclear technology’s apparent complexity. At its core, a nuclear power plant is an elaborate steam generator: nuclear fission heats water, steam spins turbines, and electricity flows to the grid. The physics has not fundamentally changed since the 1950s; what varies across reactor designs are the layers of safety equipment wrapped around this basic heat-exchange process. These safety systems consist of redundant pumps, pipes, valves, and sensors. A plant's safety systems typically include multiple independent equipment sets—called trains—each capable of performing critical functions like emergency cooling. Economic logic demands replicating these complex safety architectures rather than reinventing them for each project, but the West has repeatedly failed to do so.

This is where design innovation can obstruct nuclear development. France's European Pressurized Reactor (EPR), developed in the early 1990s as an advanced evolutionary design, added a fourth safety train to the standard three-train configuration. [3] The rationale seemed sound: avoid costly shutdowns for maintenance by always having a backup system available. But this single decision substantially increased the number of safety system components, creating severe supply chain bottlenecks. Each new, unique component requires custom engineering, regulatory approval, and specialized manufacturing. The result was as expected: France’s EPR design—currently deployed in France, Finland, and the United Kingdom—has experienced massive delays and cost overruns across all three implementations, transforming what was meant to be a standardized and exportable reactor into a series of expensive, custom-built prototypes. [4]

This pattern of design innovation impeding commercial viability is not unique to nuclear energy: aviation history offers the perfect parallel. The Concorde was the pinnacle of aerospace engineering with its supersonic speed, cutting-edge materials, and revolutionary design. However, it was commercially unsustainable due to its complexity and operating costs, leaving it relegated to museums. [5] The Boeing 747, by contrast, was less glamorous but vastly more scalable. Built on proven technology and standardized components that suppliers could produce efficiently, the 747 dominated international aviation for half a century not through radical invention, but through economic replication. [6]

While design innovations in nuclear have often backfired, process innovations have historically yielded measurable productivity gains. Prefabricated steel rebar modules shipped to construction sites can cut installation time by up to seventy-five percent and manufacturing time up to twenty percent. [7] Process innovation is also gaining traction with 3D printing of the replacement components for maintenance and repairs. Today, nearly all reactor components have existing 3D models that enable rapid production of replacements with short lead times, reducing reactor downtime. This dichotomy between design and process innovation offers a critical lens for understanding developments in the nuclear industry.

As supply chains and construction play a role in determining market competitiveness, market dominance will be secured by the players who master scalable, repeatable design, not those with the most advanced bespoke technology. This principle explains how China, building two standardized reactor types at scale, achieves construction times under seven years, [8] while Western projects pursuing novel designs routinely exceed fifteen years. EPR projects at Flamanville (France) and Olkiluoto (Finland), for example, experienced massive delays and cost overruns. [9] The EPR was originally conceived as a standardized, exportable reactor, but its design complexity and divergent national regulatory requirements resulted in a series of unique engineering challenges. This raises a critical question: if process standardization is so obviously advantageous, why does the West struggle to achieve it? The answer lies not in technological capability but in structural failures of financial and political support. Standardization only works at scale, and scale requires sustained, multi-project construction programs that only robust state backing can enable.

The Financial Reality: State Support as Nuclear Industry Lifeline

Perhaps no example better illustrates the decisive role of state backing than France's nuclear energy program. Areva, the French state-owned company that designed and built the EPR, effectively failed as a commercial enterprise in 2016-2017 after massive cost overruns and delays on its FOAK EPR projects. [10] However, because France considers nuclear capability a strategic national asset, it did not allow the company to collapse. Instead, the government orchestrated a complete bailout and restructuring, absorbing tens of billions of euros in losses and splitting the company into two state-backed entities: Orano for the fuel cycle and Framatome for reactor construction. Framatome operates today only because it was rescued through total state intervention, a lifeline unavailable to private vendors. [11]

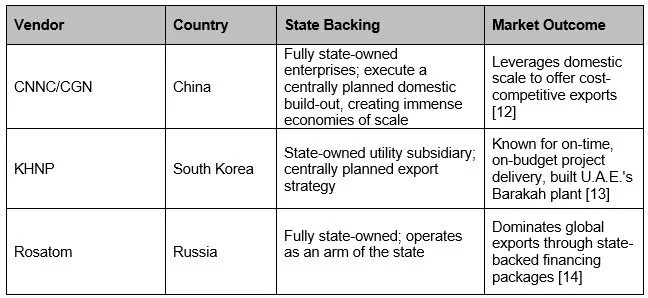

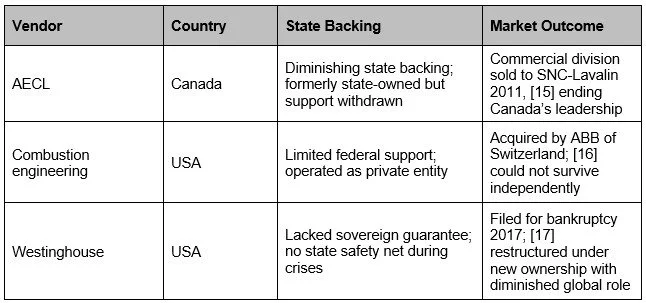

State support of this magnitude can determine whether nuclear energy vendors succeed or fail. State backing goes far beyond political rhetoric: it includes construction loans, loan guarantees, and direct government investments to share the risks and costs of nuclear construction. While many governments provide some level of backing for large energy projects, the nature, scale, and consistency of that support create a stark divide in the global nuclear industry. Vendors with sustained state backing like Russia's Rosatom and China's CNNC dominate export markets and routinely deliver projects on time and within budget. Meanwhile, firms exposed to market forces like the U.S.’s Westinghouse and Canada’s AECL have faced bankruptcy, privatization, or collapse. State-backed vendors can absorb cost overruns and delays through government guarantees, while private vendors must bear these risks alone, a disadvantage that has proven to be decisive in the capital-intensive nuclear sector. The following tables separate major players into two distinct categories based on the extent of state support they receive.

Group A: Vendors with Extensive State Backing

Group B: Vendors with Limited State Backing

The comparison between these two groups reveals a fundamental vulnerability for nuclear vendors operating without robust state backing. The financial structure of nuclear projects creates formidable challenges: construction timelines exceeding a decade, costs reaching tens of billions of dollars, and payback periods stretching over twenty years. This combination is deeply unattractive to private capital seeking faster returns.

This financial reality highlights a deeper divergence in economic philosophy. Countries that treat their nuclear industry as a strategic national asset, like Russia and China, operate with a different playbook. A single, state-backed "national champion" is tasked with ensuring energy security and projecting geopolitical influence, with profit being a secondary consideration. In contrast, the U.S. and U.K. have liberalized energy markets where vendors are often private companies obligated to shareholders. In this fragmented market, the state is more hesitant to provide the kind of continuous, large-scale financial guarantees needed, leaving these firms exposed to the immense risks of the nuclear business. In the long term, this compounded disadvantage leads to more sporadic nuclear projects, which degrades the West's industrial “muscle memory”—the workforce skills and supply chain expertise crucial for sustained nuclear development. [18]

Industrial Muscle Memory: The Backbone of Nuclear Competitiveness

The absence of sustained state backing creates a vicious cycle beyond financial vulnerability. Without continuous project pipelines, the West has experienced significant erosion of the industrial capabilities essential for nuclear construction. The global nuclear industry saw a boom in the 1970s following the oil crisis, [19] but new construction largely ceased by the late 20th century, creating a multi-decade hiatus before the current tentative revival. This pause has had severe consequences for the industry's muscle memory across western countries like the U.S., U.K., and France, who have extended gaps in their construction timelines:

In the U.S., Watts Bar 1 entered service in 1996. In 2016 the Watts Bar 2, a long-delayed project originally started in 1973, came online. The Watts reactors were the last reactors to come online in 30 years, [20] until the recently completed Vogtle Units in Georgia (2023-2024). [21]

The U.K.’s last plant, Sizewell B, came online in 1995, [22] with Hinkley Point C still years from operation—now expected between 2029 and 2031 after multiple delays. [23]

Even in France, the one-time leader in nuclear construction, the Chooz B2 reactor started operation in 2000, creating an almost 25-year gap before Flamanville 3 connected to the grid in 2024. [24]

A quarter-century gap represents an entire generation of specialized engineers, project managers, and skilled technicians who have retired or left the industry. This workforce challenge persists today: the U.S. nuclear sector has 23 percent fewer workers under age 30 than the broader energy workforce, with a significant portion of the aging workforce expected to retire over the next decade. [25] The combined tangible effects are starkly visible in the struggles of recent Western projects, where skills-related failures, from faulty welding to fragile supply chains, have led to well-documented delays and cost overruns. [26]

In stark contrast to the West's prolonged pause, China, Russia, and South Korea maintained and grew their capabilities through state-backed construction programs:

China has embarked on the most ambitious and continuous nuclear construction program in history over the last 30 years. [27] It currently has fifty-eight operational reactors and thirty-three more under construction. China’s relentless "fleet mode" approach allows them to drastically reduce engineering costs after the first few units and cultivate an unparalleled supply chain.

Russia’s Rosatom has leveraged a continuous pipeline of domestic projects and a robust export model. It has thirty-six operational reactors and seven under construction domestically. Crucially, state-owned corporation Rosatom is also building nineteen reactors abroad in countries like Turkey, India, China, and Egypt, keeping its entire supply chain and skilled workforce consistently engaged. [28]

South Korea pursued a highly disciplined domestic program, resulting in twenty-six operational reactors, with another three under construction. [29] This constant activity perfected their project execution, culminating in the successful on-time, on-budget delivery of four nuclear reactors at the Barakah plant in the U.A.E. [30]

Ultimately, the divergence in outcomes reveals a well-established principle: industrial capability is a perishable skill that cannot be shelved and retrieved decades later. Successful players treat their nuclear muscle memory as requiring constant training, while Western incumbents have allowed it to atrophy.

Strategic Reforms for Western Nuclear Revival: A Closing Window

The West stands at a critical crossroads in nuclear energy: continued hesitation or fragmented efforts threaten irreversible damage to global energy security and geopolitical influence. Restoring Western nuclear leadership will depend on coordinated reforms such as targeting innovation strategies, financial frameworks, and sustained industrial capabilities. Such reforms operate not in isolation but as an interconnected system; weaknesses in any one area compromise the entire nuclear enterprise.

The recent surge in private capital toward Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) might appear to circumvent some of these challenges. [31] SMRs are typically defined as advanced reactors with standardized factory production and transportable components. [32] Their appeal lies in reduced complexity and lower upfront capital requirements. However, the core principles identified in this paper apply equally to SMRs. Companies leading on SMR innovation will need to work on prioritizing replication over design innovation, ensuring sustained state backing, and maintaining continuous industrial capabilities. Without these structural supports, even modular designs risk commercial failure.

Confronted with these substantial challenges, the following targeted policy measures offer a critical roadmap for the West to seize this opportunity and reclaim the global leadership in nuclear energy:

Prioritize programmatic replication: Commit to multi-unit procurement of standardized reactor designs before initiating construction. South Korea's approach of building the same APR-1400 design repeatedly before exporting to the U.A.E. demonstrates how sustained volume enables cost reduction and supply chain development.

Establish unwavering state-backed financial frameworks: Develop sovereign guarantees and long-term co-investment schemes to de-risk nuclear projects. France's restructuring of Framatome and the UK's model for Hinkley Point C financing show that large-scale nuclear energy requires direct state participation, not just loan guarantees.

Invest aggressively in workforce and supply chain revitalization: Launch dedicated training programs tied to guaranteed employment contracts across multi-reactor construction pipelines. The contrast between France's welder shortages and China's sustained workforce development illustrates that industrial capability requires continuous practice. Commit substantial resources to personnel retention and supply chain resilience initiatives that restore industrial competence and close generational skill gaps.

Recast nuclear power as a strategic national asset: Embed nuclear capability within national security frameworks to ensure bipartisan commitment beyond electoral cycles. Treating nuclear construction capability as critical infrastructure, comparable to defense production, secures the political will necessary to sustain multi-decade programs and mobilize public and private sector collaboration.

By implementing these targeted reforms with urgency and coherence, western states can reverse decades of decline and rebuild competitive nuclear capabilities. The window is narrowing; China and Russia continue to extend their lead with each completed project. Without systematic reform, the West risks permanent relegation to nuclear irrelevance, surrendering not only commercial opportunities but strategic autonomy in clean energy production. The choice is stark: commit to sustained, coordinated action now, or accept permanent dependence on geopolitical rivals for nuclear technology and expertise.

About the authors

Ibrahim Mustafayev is a climate & energy consultant and Yale School of Management alumnus (MBA 2023). At Boston Consulting Group, he was the only North American-based consultant seconded to the COP29 Presidency, advising on climate strategy and energy transitions. He currently advises the U.S.-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce on energy cooperation and conducts research on nuclear energy competitiveness and infrastructure development.

Orkhan Akbarov is a PSA/PRA Engineer at EDF (U.K.) specializing in probabilistic safety assessment and nuclear system risk modeling. He holds a Master's degree in Nuclear Engineering from Paris Saclay University and has contributed to safety assessment projects for nuclear facilities in France and the United Kingdom. His work focuses on risk-informed design, hazard analysis, and regulatory compliance.

Endnotes

[1] World Nuclear Association, “Plans For New Reactors Worldwide,” accessed September 2025, https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/plans-for-new-reactors-worldwide.

[2] This paper defines the West as advanced industrialized democracies in North America and Europe with market-oriented economies

[3] U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, “EPR Project overview,” Design Certification Application Review, September 2022, https://www.nrc.gov/reactors/new-reactors/large-lwr/design-cert/epr/overview.

[4] Greenpeace France, The Cost of “New Era” Nuclear: The Unbearable Lightness of EDF, March 2024, 2-3, https://cdn.greenpeace.fr/site/uploads/2024/03/Summary-Report-The-cost-of-new-era-nuclear-Greenpeace-2024.pdf.

[5] Justin Hayward, "The Rise & Fall Of Concorde," Simply Flying, February 18, 2021, https://simpleflying.com/concorde-rise-and-fall/.

[6] Stephen Dowling, "The Boeing 747: The Plane That Shrank the World," BBC Future, September 19, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20180927-the-boeing-747-the-plane-that-shrank-the-world.

[7] Rob Hakimian, “Ever larger pieces being manufactured offsite for construction of Hinkley Point C,” New Civil Engineer, July 30, 2024, https://www.newcivilengineer.com/latest/ever-larger-pieces-being-manufactured-offsite-for-construction-of-hinkley-point-c-30-07-2024/.

[8] Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), “How Innovative Is China in Nuclear Power?” June 16, 2024, https://itif.org/publications/2024/06/17/how-innovative-is-china-in-nuclear-power/.

[9] Frank Bass, “European Pressurized Reactors (EPRs): ‘Next Generation’ Design Suffers from Old Problems,” IEEFA, February 2, 2023, https://ieefa.org/resources/european-pressurized-reactors-eprs-next-generation-design-suffers-old-problems.

[10] EDF, "Signing of Definitive Binding Agreements for the Sale of AREVA NP's Activities to the EDF Group," December 21, 2017, https://www.edf.fr/en/the-edf-group/dedicated-sections/journalists/all-press-releases/signing-of-definitive-binding-agreements-for-the-sale-of-areva-np-s-activities.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Nuclear Business Platform, "China’s Nuclear Supremacy: Why Global Investors Can’t Ignore the World’s Largest Reactor Pipeline," October 4, 2025, https://www.nuclearbusiness-platform.com/media/insights/china-nuclear-supremacy

[13] Samo Burja, "South Korea Builds Nuclear Plants Quickly and Cheaply," Bismarck Brief, October 4, 2024, https://brief.bismarckanalysis.com/p/south-korea-builds-nuclear-plants.

[14] Nuclear Energy Institute, “Russia and China Are Dominating Nuclear Energy Exports. Can the U.S. Catch Up?” 2021, https://www.nei.org/CorporateSite/media/filefolder/resources/fact-sheets/Russia-and-China-Are-Dominating-Nuclear-Energy-Exports-Can-the-U-S-Catch-Up.pdf.

[15] Julie Gordon and Nicole Mordant, "Canada privatizes nuclear unit; sells to SNC," Reuters, June 29, 2011, https://www.reuters.com/article/world/us/canada-privatizes-nuclear-unit-sells-to-snc-idUSTRE75S6HW/.

[16] Neil Springer, "Swiss Company to Acquire Combustion Engineering," S&P Journal of Commerce, November 13, 1989, https://www.joc.com/article/swiss-company-to-acquire-combustion-engineering-5524550.

[17] Tom Hals, Makiko Yamazaki, and Tim Kelly, "Huge nuclear cost overruns push Toshiba's Westinghouse into bankruptcy," Reuters, March 29, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/business/huge-nuclear-cost-overruns-push-toshibas-westinghouse-into-bankruptcy-idUSKBN17006K/.

[18] International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), “Knowledge Management for Nuclear Research and Development Organizations,” TECDOC No. 1675, Vienna: IAEA, 2013, https://www.iaea.org/publications/8644/knowledge-management-for-nuclear-research-and-development-organizations.

[19] John R. Lovering et al., "Historical Construction Costs of Global Nuclear Power Reactors," Energy Policy 91 (2016): 371-382, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421516300106/.

[20] Tennessee Valley Authority, "Watts Bar Nuclear Plant," accessed September 2025, https://www.tva.com/energy/our-power-system/nuclear/watts-bar-nuclear-plant.

[21] Southern Nuclear, "Plant Vogtle: Alvin W. Vogtle Electric Generating Plant," accessed September 2025, https://www.southernnuclear.com/our-plants/plant-vogtle.html.

[22] Power Technology, "Power Plant Profile: Sizewell B, UK," accessed September 2025, https://www.power-technology.com/marketdata/power-plant-profile-sizewell-b-uk/.

[23] EDF, "Hinkley Point C Update," January 23, 2024, https://www.edf.fr/en/the-edf-group/dedicated-sections/journalists/all-press-releases/hinkley-point-c-update-1.

[24] NS Energy Business, "Chooz B Nuclear Power Plant," accessed September 2025, https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/projects/chooz-b-nuclear-power-plant/.

[25] U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Nuclear Energy, "5 Workforce Trends in Nuclear Energy," August 28, 2024, https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/5-workforce-trends-nuclear-energy.

[26] David Dalton, “Flamanville-3 / EDF Announces Three-Year Delay Due To Weld Repairs,” NucNet, July 26, 2019, https://www.nucnet.org/news/edf-announces-three-year-delay-due-to-weld-repairs-7-5-2019/.

[27] World Nuclear Association, “Nuclear Power in China,” accessed September 2025, https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-a-f/china-nuclear-power/.

[28] World Nuclear Association, “Nuclear Power in China,” accessed September 2025, https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-a-f/china-nuclear-power/.

[29] World Nuclear Association, “Nuclear Power in South Korea,” accessed September 2025, https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/country-profiles/countries-o-s/south-korea/.

[30] Seok-min Oh, “S. Korean-built nuclear reactor successfully connected to UAE power grid,” Yonhap News Agency, March 24, 2024, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20240324000800320/.

[31] International Energy Agency (IEA), “The Path to a New Era for Nuclear Energy,” January 16, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/the-path-to-a-new-era-for-nuclear-energy.

[32] International Atomic Energy Agency, "Small Modular Reactors," IAEA Topics, accessed September 2025,https://www.iaea.org/topics/small-modular-reactors.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect the opinions of the editors or the journal.