Why Has Central Asia Resisted Democratization? (Volume 21, Issue 1)

Vladimir Putin in talks with the President of Uzbekistan. Source: Kremlin

By Munisa Djumanova

1. Introduction: Central Asia’s Authoritarian Resilience in a Post-Soviet Context

In July 2022, protests erupted in Karakalpakstan, an autonomous region within Uzbekistan, in response to proposed constitutional amendments. The amendments sought to reduce the region's autonomy and limit its independence. The Uzbek government’s harsh response, which resulted in at least twenty-one fatalities, serves as a prominent example of authorities’ continued resistance to democratic reform and transparency. Since then, Uzbek authorities have intensified their crackdown on activists, imposing severe prison sentences on senior figures advocating for Karakalpak autonomy. Despite international condemnation, no Uzbek officials have been held accountable, signaling the country’s prioritization of authoritarian political stability—defined here as the preservation of regime control and elite dominance—over democratic accountability. [1]

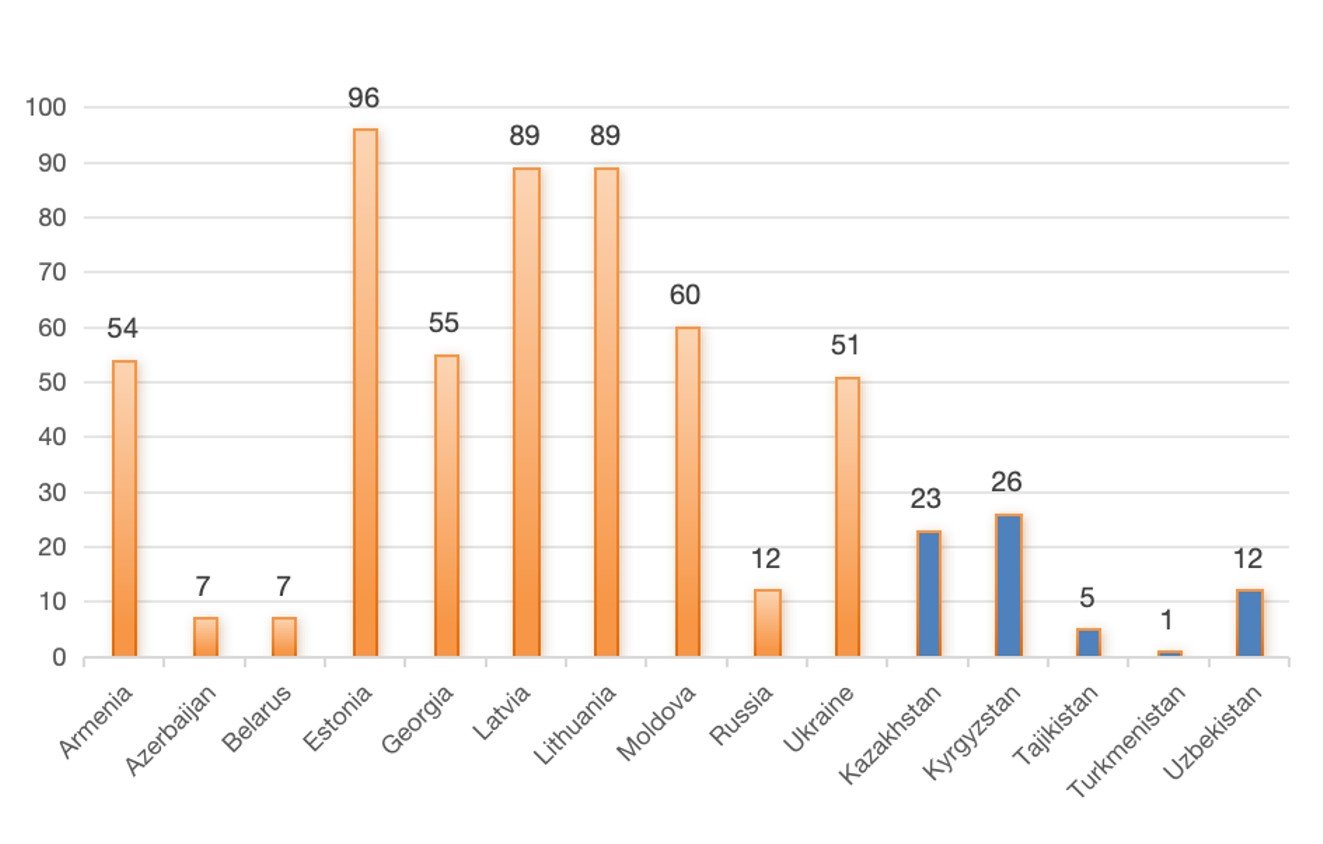

This trend is not unique to Uzbekistan. Across Central Asia, governments rooted in the Soviet legacy maintain centralized control through authoritarian practices, stifling democratic transitions. Three decades after the fall of the Soviet Union, authoritarian regimes dominate the region, where only the three Baltic states are classified as "Free" by Freedom House. [2] In contrast, nations like Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan are rated as "Not Free," with Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan scoring eleven and twenty-three out of one hundred, respectively (Table 1). Kyrgyzstan, despite brief democratic openings, scores only twenty-eight, well below the threshold for partial democracy.

Table 1: Freedom House Index Comparison (2025) between Eastern Europe (orange) and Central Asia (blue)

In states like Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, restrictive laws on media freedom empower officials to censor information without judicial oversight. [3] Yet, public discontent persists, as large-scale protests continue in response to economic and political grievances. In Kazakhstan, for example, mass demonstrations over fuel prices in 2022 resulted in over 200 deaths due to security force crackdowns. These violent responses reflect a regional pattern: Central Asian governments prioritize regime and political stability—rather than democratic reform or transparency—particularly to protect elite interests and avoid power-sharing, even in the face of public unrest. This pattern raises a critical question in comparative politics: why have Central Asian regimes resisted democratization while other post-Soviet regions, such as Eastern Europe, embraced democratic transitions?

This paper argues that domestic elite cohesion and external geopolitical support combine to sustain authoritarian resilience in Central Asia, limiting the prospects for democratization. Internally, centralized power structures and elite bargaining reinforce authoritarian resilience, constraining democratic opportunities. Externally, major regional powers like China and Russia support compliant regimes through economic investments, political endorsements, and security cooperation, prioritizing strategic regional stability over democratic change.

Through cross-regional comparisons, particularly with the Middle East and Southeast Asia, the paper shows that the regimes deploy controlled liberalization and "hybrid" reforms to maintain power. These strategies, alongside strategic alliances with organizations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), protect authoritarian stability from democratizing pressures, emphasizing the unique trajectory of Central Asia’s political landscape.

To understand this resistance, the paper draws on democratization theory, authoritarian resilience, and geopolitical influence. In Central Asia, resource wealth supports authoritarianism by reducing dependence on popular support, while elite-centered strategies help regimes manage public demands without undermining elite authority. Stability, as pursued in the region, is not synonymous with good governance or development, but with preserving the status quo through top-down control.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1 Democratization Theory: Limitations in Central Asia

Central Asia has diverged sharply from the expectations laid out in Huntington’s Third Wave of Democratization, which links democratic transitions to economic development, civil society growth, and the diffusion of global democratic norms. [4] After the Soviet Union’s collapse, Eastern Europe exemplified this trend as reforms like perestroika and glasnost helped catalyze democratic transitions. However, Central Asia has diverged sharply from this trajectory. As Akchurina notes, Central Asian leaders prioritized stability and consolidated power through elite networks and centralized authority over political reforms. [5] This divergence highlights the limitations of traditional democratization theories in explaining the unique political trajectory of Central Asia, where democratic norms have limited impact.

Matveeva’s work, Democratization, Legitimacy, and Political Change in Central Asia, expands on the variations in democratization, arguing that Central Asian regimes derive legitimacy less from democratic reforms and more from the goal of stability. Unlike Eastern Europe, where democratic transitions were transformative, Central Asian regimes emphasize continuity. [6] These observations challenge the universal applicability of democratization theory, which tends to overlook how stability-based legitimacy and regional influences, such as those from Russia and China, shape Central Asia’s political landscape.

2.2 Authoritarian Resilience: Elite Networks and Internal Structures

Scholars like Schatz and Anceschi explore how elite networks, patronage systems, and clan politics reinforce authoritarian structures in Central Asia. [7] Akchurina adds that state-building in Central Asia historically prioritized control over pluralism, where elite-driven reforms deepened centralized power rather than promoting democratic participation. [8] While these scholars clarify the internal factors of authoritarian resilience, they often underplay the strategic external alliances that further reinforce these regimes.

This study extends their analysis by examining how Central Asian elites leverage support from external powers like Russia and China to fortify their internal control. By blending elite networks with strategic external alliances, Central Asian leaders have developed a resilient form of authoritarianism that is both internally cohesive and externally supported, complicating democratization efforts in the region.

2.3 Alternative Models of Authoritarian Resilience

While Central Asian regimes have maintained authoritarian control through elite-centered governance and foreign backing, a brief comparison with Southeast Asia offers insight into alternative models of regime durability and democratization. Southeast Asia, like Central Asia, features hybrid regimes, resource-based economies, and histories of strongman rule—yet the region displays greater variation in democratic outcomes. For example, Indonesia transitioned from Suharto’s authoritarian “New Order” regime to a functioning electoral democracy after the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis. This shift was catalyzed by elite fragmentation, student protests, and growing civil society activism, showing that even patrimonial and military-backed regimes can experience democratization when state legitimacy erodes and social mobilization intensifies. [9]

Conversely, Malaysia and Singapore have retained semi-authoritarian systems marked by dominant-party rule, but with relatively higher degrees of institutional accountability and legal transparency. Malaysia’s The United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) lost its longstanding parliamentary majority in 2018, demonstrating the presence of competitive elections and alternation of power, despite elite patronage networks. [10] Singapore, although governed by the People’s Action Party since independence, has institutionalized technocratic governance and rule of law to a greater extent than most Central Asian states. These regimes prioritize “performance legitimacy” over coercion alone, using service delivery, legal reform, and education as tools of regime stability.

In contrast, Central Asian regimes often rely more heavily on repression, opaque patronage, and foreign alliances for durability. Civil society remains fragmented, opposition is suppressed, and legal frameworks are shaped to prevent political competition. The comparison suggests that while patrimonialism and elite politics exist in both regions, the presence of relatively autonomous institutions, legal accountability, and vibrant civil societies can create gradual openings for democratization—as seen in parts of Southeast Asia. These factors are largely absent in Central Asia, underscoring the region’s distinct authoritarian trajectory.

2.4 Geopolitical Influence: The Role of Russia and China

External actors, particularly Russia and China, play a pivotal role in supporting authoritarian regimes in Central Asia. Alexander Cooley’s Great Games, Local Rules argues that these powers provide economic, military, and political support to Central Asian leaders, perceiving the region as a crucial buffer zone where stability trumps democratic change. [11] This support includes economic investments and “soft power” tactics, such as cultural exchanges and educational programs, which align public opinion with authoritarian governance models.

Akchurina further highlights how these powers’ influence intertwines with Central Asia’s elite networks, reinforcing existing patronage structures and strengthening the regime's capacity to suppress dissent. [12] Her argument suggests that external powers reinforce, rather than reshape, the domestic architecture of authoritarianism. However, this paper posits that these alliances operate in a more reciprocal manner: Central Asian leaders strategically leverage ties with Russia and China to negotiate resources, legitimize their rule, and insulate themselves from Western democratizing pressures. Thus, while Akchurina emphasizes external reinforcement of domestic elites, this paper stresses the agency of Central Asian regimes in instrumentalizing geopolitical partnerships to consolidate their own authoritarian stability.

2.5 Toward a Dual Framework of Authoritarian Resilience

By synthesizing insights from democratization theory, authoritarian resilience, and geopolitical influence, this paper proposes a dual framework to explain Central Asia’s political landscape. This framework considers both the internal dynamics of elite cohesion and the strategic alliances with Russia and China as mutually reinforcing factors that resist democratization pressures. Specific case studies, such as Kazakhstan’s clan-based patronage networks and Uzbekistan’s strategic alignments with Russia, demonstrate how these internal and external dynamics interact to produce a self-sustaining authoritarian system in Central Asia.

This dual framework underscores the need for tailored democratization strategies that address both the domestic and international dimensions of authoritarian resilience. Traditional democratization approaches may require significant adaptation to contend with the complex geopolitical and cultural realities unique to Central Asia, thereby filling a critical gap in the current scholarship.

This study builds on, but also departs from, earlier scholarship on Central Asia’s political resilience. Works such as Mariya Omelicheva’s Democracy in Central Asia and Edward Schatz’s studies on soft authoritarianism have effectively outlined the roles of security interests, elite patronage, and geopolitical alignment in explaining the region’s authoritarian persistence. [13] However, this paper contributes to the existing literature in three key ways. First, it develops a dual framework that links internal elite cohesion with external geopolitical reinforcement—a dynamic that has become more visible in the wake of events like the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) intervention in Kazakhstan and China’s expanding Belt and Road footprint. Second, the paper advances the East Europe–Central Asia comparison, which remains underexplored in much of the existing scholarship, despite both regions sharing post-Soviet origins. Finally, it integrates recent case studies, including the 2022 protests in Kazakhstan and the constitutional crisis in Karakalpakstan, to show how authoritarian regimes adapt to challenges in real time. These contributions aim to refine the understanding of authoritarian resilience by situating it in a broader comparative and contemporary framework.

3. Authoritarian Resilience through Centralized Power and Elite Bargains

Despite the widespread democratization observed in Eastern Europe during the 1990s, Central Asia’s authoritarian trajectory began consolidating soon after the collapse of the Soviet Union. This divergence is particularly puzzling given that in the early post-independence period, Russian and Chinese influence in the region was relatively weak, while Western governments and institutions actively promoted liberal reform. Organizations such as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and USAID provided technical assistance for elections, civil society, and legal reform. [14]

Yet democratic momentum stalled due to three interlinked factors: the top-down nature of independence, the weakness of civil society and political mobilization, and leaders’ prioritization of state-building over political reform. First, independence did not emerge from popular revolutions but from a top-down transfer of authority, allowing former Soviet elites to retain power under nationalistic narratives. [15] Second, weak civil societies, low political mobilization, and the absence of organized opposition movements meant there was little grassroots pressure for democratization. [16] Finally, in the context of severe economic crises, leaders framed “stability” as a paramount objective, using it to justify delaying political reforms and entrenching authoritarian governance early on.

This foundational period shaped the trajectory of Central Asian politics for decades to come. Unlike in Eastern Europe, where democratic institutions were built during a similar transitional moment, Central Asia’s leaders entrenched personalistic rule and elite patronage networks. By the early 2000s, external actors like China and Russia increasingly filled the regional power vacuum, reinforcing these authoritarian patterns with economic and security support.

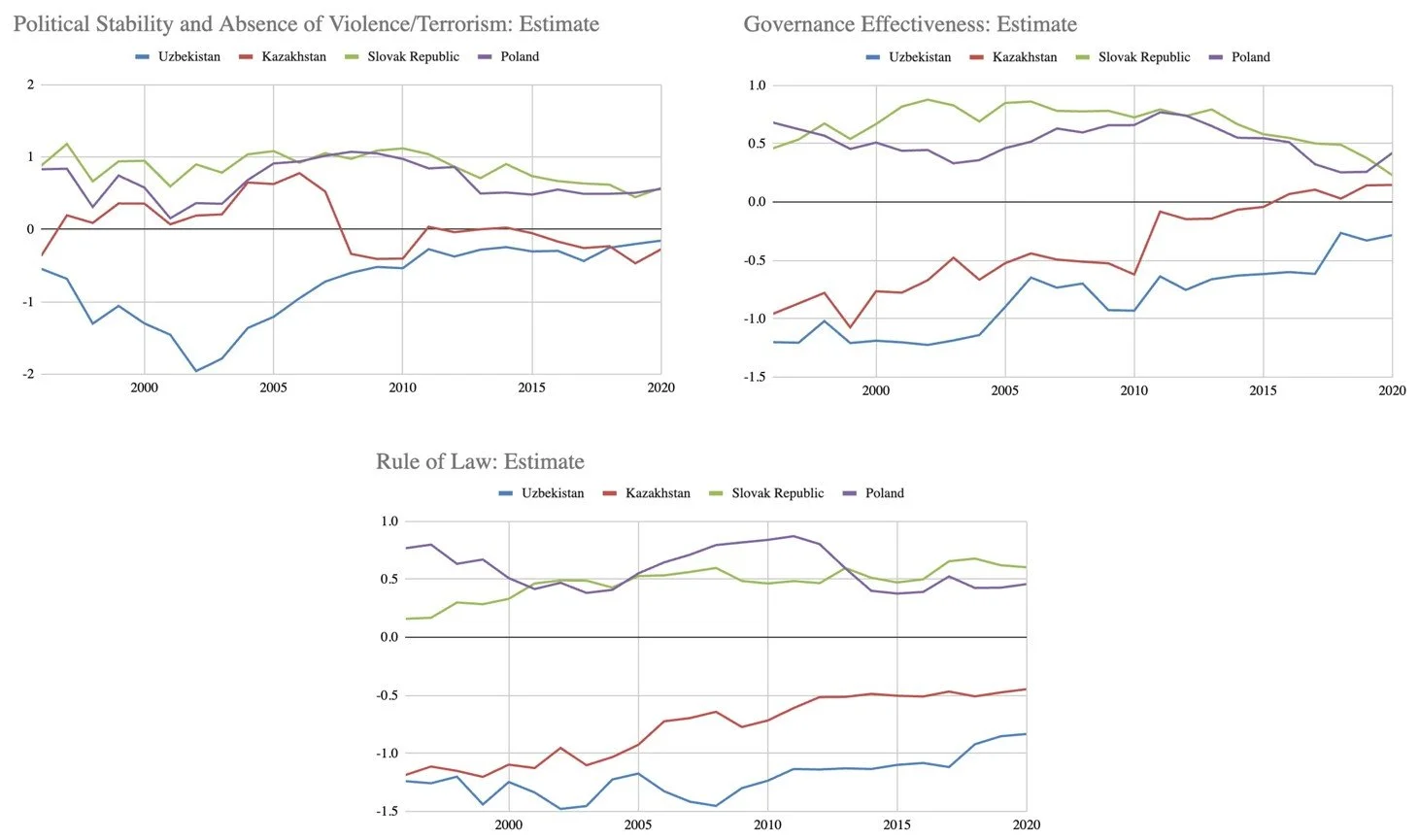

The resilience of authoritarian regimes in Central Asia, particularly in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, stems from centralized power, elite loyalty, and carefully managed reforms. While many Eastern European countries transitioned to democracy after the Soviet Union's collapse, Central Asian leaders have maintained control through strategies that prioritize regime continuity and elite cohesion over political openness. Graph 1 illustrates these dynamics: Uzbekistan experienced a sharp increase in violence and terrorism in the early 2000s, resulting in a substantial drop in political stability, while Kazakhstan, Poland, and Slovakia saw smaller fluctuations within a higher range. In terms of governance effectiveness and rule of law, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan improved over time but remain below zero, whereas Poland and Slovakia maintain higher scores overall.

Graph 1: Comparison of regime stability (1996-2020)

Data source: World Bank. [17]

These trends suggest that Central Asian regimes sustain stability not through robust institutions or formal governance, but through elite networks, patronage, and selective reforms. For instance, gradual improvements in governance effectiveness reflect targeted administrative reforms and limited economic modernization, rather than broad institutional accountability. Similarly, the modest gains in rule of law indicate selective legal enforcement that reinforces elite authority rather than empowering citizens or independent institutions. Even when political stability dips—as in early 2000s Uzbekistan—the regime’s internal cohesion and control over key sectors allowed for rapid recovery, demonstrating the ability to absorb shocks without democratizing. Overall, the graphs reveal that Central Asia exemplifies a model of authoritarian resilience based on internal power structures and managed reforms, in contrast to Eastern Europe, where formal institutions and rule of law underpin political stability and democratization.

Kazakhstan exemplifies this model of authoritarian resilience. Although former President Nursultan Nazarbayev officially stepped down in 2019, he kept significant power as the “Leader of the Nation” and head of the Security Council. [18] His successor, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, showed a similar commitment to stability over reform, especially during the 2022 protests sparked by rising fuel prices. In response to the unrest, Tokayev requested support from the CSTO to restore order, highlighting his reliance on elite loyalty and external allies. [19] Unlike Eastern European protests, which often drove political change, Kazakhstan’s response reinforced centralized control rather than embracing calls for reform.

Similarly, in Uzbekistan, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has similarly pursued selective reforms to project an image of modernization without altering the country’s authoritarian structure. After taking office in 2016, he introduced modest changes, like reducing forced labor and easing some media restrictions. [20] However, the 2021 presidential and 2023 parliamentary elections showed the limits of these reforms, as genuine opposition remained largely absent. Mirziyoyev’s approach of “managed democracy” signals some openness while maintaining strong central authority. [21] This contrasts with Eastern European countries like Slovakia and the Czech Republic, where competitive multi-party systems allowed real political change and were evident in Graph 1 as well.

From literature, Schatz and Anceschi explain Central Asian authoritarian resilience as grounded in economic incentives and elite patronage. [22] For example, Kazakhstan’s control over oil resources allows it to reward key elites, strengthening their loyalty to the regime. Similarly, Uzbekistan’s economic liberalization has benefited elites close to the government, reinforcing their support and stabilizing the system.

A comparison with Eastern Europe highlights these structural differences. Baltic countries, driven by EU integration goals, pursued democratic reforms to align with Western standards. In contrast, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, more closely aligned with Russia and China, face little external pressure to democratize. These geopolitical alignments matter: partnerships with powers that prioritize stability over reform allow Central Asian leaders to consolidate authority without facing the kind of external democratic conditionality that shaped Eastern Europe’s post-Soviet trajectory.

This model of “authoritarian upgrading” involves selective reforms that create an image of progress without real power-sharing. [23] Kazakhstan rewards loyal elites with oil wealth, while Uzbekistan limits political competition, presenting controlled openness. These adaptive strategies contrast sharply with Eastern Europe’s democratic transitions, underscoring the distinct paths post-Soviet states have taken.

While elite cohesion and top-down control explain much of Central Asia’s authoritarian durability, the absence of bottom-up pressure has also been crucial in limiting democratic openings. Unlike Eastern Europe, where widespread protests and organized opposition helped catalyze regime change, Central Asia’s societies are marked by weaker civil society institutions, lower levels of political mobilization, and higher barriers to collective action. Post-Soviet social contracts in the region have often prioritized basic service delivery and economic stability in exchange for political quiescence. [24] In countries like Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, repression and surveillance have further weakened grassroots activism, while in Kazakhstan, opposition groups remain fragmented or co-opted by the state. [25]

January 2022 protests in Kazakhstan, which began over fuel price hikes but quickly evolved into broader political unrest, briefly disrupted this dynamic. The scale and intensity of the protests, coupled with slogans demanding systemic change, revealed growing popular frustration with entrenched elite rule. Yet the government's militarized response—backed by the CSTO—and subsequent superficial reforms demonstrated the regime's ability to contain dissent without undergoing democratization. Rather than signaling a democratic opening, the crisis reinforced elite unity and highlighted the persistent limits of bottom-up mobilization. These dynamics underscore that even in moments of visible instability, Central Asia’s authoritarian resilience remains deeply entrenched.

4. Geopolitical Competition and the Influence of China and Russia

The resilience of authoritarian regimes in Central Asia is strongly supported by geopolitical competition, with China and Russia playing key roles in sustaining these governments. Unlike Eastern Europe, where the European Union (EU) promoted democratization through economic and political integration, Central Asia’s political stability is bolstered by its influential neighbors, who prioritize stability over democratic reforms. [26] This support is best understood through dependency theory and the concept of strategic stability, both of which explain how reliance on China and Russia strengthens Central Asia’s political structures, protecting the region from democratization pressures. [27]

Beyond material support, China and Russia perceive democratization in Central Asia as a direct challenge to regime security and regional authority. Both powers prioritize maintaining a regional order composed of predictable, like-minded authoritarian regimes that can serve as buffers against Western influence and internal instability. Russia, particularly since the Color Revolutions and the 2014 Euromaidan protests in Ukraine, has viewed democratic transitions in post-Soviet spaces as foreign-instigated threats to its sphere of influence. [28] Moscow’s strategy involves not only military backing, as seen in Kazakhstan’s 2022 unrest, but also media narratives and soft power that delegitimize liberal democratic models in favor of “sovereign democracy” or managed pluralism.

China’s stance is similarly driven by concerns over internal stability. Beijing fears that democratic movements in neighboring Central Asian states could embolden separatist sentiments in Xinjiang or inspire domestic unrest more broadly. [29] The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), co-founded by China and Russia, has increasingly served as a mechanism for coordinating regional responses to what both powers call the “three evils”: terrorism, separatism, and extremism—often broadly applied to any form of democratic activism. [30] In this context, democratization is not just undesirable but destabilizing, threatening both the domestic legitimacy and international strategy of these two major actors. Their support for Central Asian authoritarian regimes is thus not passive alignment but a deliberate bulwark against political pluralism on their peripheries.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) exemplifies how economic dependency fosters authoritarian resilience in Central Asia. Through extensive infrastructure projects and significant investments in sectors like energy and transportation, China has integrated these economies into its broader strategic vision, promoting development without demanding the democratic reforms often tied to Western financial aid. [31] Countries such as Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan are increasingly economically reliant on China, making it a top trading partner across the region. [32] This dependency allows authoritarian leaders to pursue economic growth while maintaining political control, reducing the leverage of Western democracies and strengthening regimes that prioritize stability over democratization.

Russia’s influence further deepens this dependency and secures authoritarian stability across the region. Unlike Eastern Europe, where many countries distanced themselves from Russian influence following the Soviet collapse, Central Asia remains closely aligned with Russia, which exercises significant economic and military influence. [33] Russia’s support became particularly evident during the 2022 protests in Kazakhstan, when unrest initially sparked by fuel price hikes quickly evolved into calls for broader political reform. In response, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev requested intervention from the CSTO, a Russia-led security alliance. The CSTO’s intervention not only suppressed domestic dissent but also underscored Russia’s commitment to defending authoritarian stability in Central Asia. [34] This level of external intervention reflects Russia’s strategic goal of preserving regional order, signaling to other Central Asian leaders that Moscow will actively support regimes that align with its vision of stability. This contrasts sharply with Eastern Europe, where popular movements and Western support for democratization led to regime transitions and institutional reform. In Central Asia, however, Russia’s readiness to intervene underlines the security it provides to authoritarian regimes, dissuading reformist efforts.

In Eastern Europe, EU engagement created powerful incentives for democratization, offering post-communist states substantial benefits in exchange for institutional reforms. EU membership provided countries like Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic with economic development, political stability, and integration into the European political system, catalyzing their transitions toward democratic governance. [35] These nations were encouraged to adopt transparent governance, judicial reforms, and multiparty political systems, driven by the promise of EU integration and its associated economic rewards. [36] In Central Asia, however, no comparable incentive structure exists, and countries like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan benefit from Chinese investments and Russian military backing without any pressure to democratize. The security and economic advantages offered by Russia and China thus empower these regimes to retain centralized authority, diminishing the urgency for reform.

This contrast between Central Asia and Eastern Europe highlights the crucial role of external actors in shaping post-Soviet political trajectories. Dependency theory explains how Central Asian authoritarianism endures: economic reliance on China enables growth and infrastructure development without requiring democratic reforms, while Russia’s strategic interest in regional stability—reinforced through military intervention and political alliances—supports the authoritarian status quo. In Eastern Europe, democratization was accelerated by the EU’s integration process, which tied economic and political benefits to institutional reform. In Central Asia, by contrast, China and Russia prioritize regime stability over political liberalization, entrenching authoritarian governance and limiting the influence of external democratizing pressures. Through the lenses of dependency and strategic stability theories, it is clear that foreign influence has reinforced authoritarian resilience in Central Asia, driving a post-Soviet political trajectory that diverges sharply from the EU-driven transitions in Eastern Europe.

5. Conclusion

The resilience of authoritarianism in Central Asia is bolstered by a combination of centralized governance structures and significant support from external powers, particularly China and Russia. In countries like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, leaders maintain stability through resource control, elite patronage, and selective reforms that enhance their authority while resisting democratization pressures. Externally, China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Russia’s strategic alliances offer these regimes economic and security benefits without the demands for political liberalization seen in Eastern Europe. This dynamic diverges sharply from Eastern European paths toward democratization, which were incentivized by EU integration and economic aid conditioned on institutional reforms.

For international actors seeking to encourage democratic progress, strategies should address both the economic dependencies and internal structures supporting authoritarianism in the region. Policy recommendations include targeted development aid with conditions for gradual governance reforms, strengthened civil society support, and regional cooperation initiatives. Engaging youth and academic exchanges could further promote democratic values and build regional networks with a vested interest in reform.

Future research might examine shifts like economic changes, generational dynamics, or civil society growth, which could gradually challenge existing power structures. While democratization in Central Asia faces formidable barriers, evolving internal dynamics and international engagement could eventually open pathways to political reform—though a gradual, managed approach remains essential to avoid destabilizing these states.

About the author

Munisa Djumanova is a 2026 MAIR candidate at Johns Hopkins SAIS, where she is pursuing a minor in governance and politics in Europe and Eurasia. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Economics from Westminster International University in Tashkent. She has interned at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center and, since 2024, has been working with the Center for Constitutional Studies and Democratic Development (CCSDD) on constitutional development and democratization in Central Asia.

Endnotes

[1] Human Rights Watch, “Uzbekistan: 2 Years On, No Justice in Autonomous Republic,” July 2024, https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/07/01/uzbekistan-2-years-no-justice-autonomous-republic

[2] Freedom House, “Regional Trends & Countries in the Spotlight,” Freedom in the World 2023, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2023/marking-50-years/countries-regions

[3] Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2023: Marking 50 Years in the Struggle for Democracy, March 2023, https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/FIW_World_2023_DigtalPDF.pdf

[4] Samuel P. Huntington, “Democracy’s Third Wave,” Journal of Democracy 2, no. 2 (Spring 1991): 12–34, https://www.ned.org/docs/Samuel-P-Huntington-Democracy-Third-Wave.pdf

[5] Viktoria Akchurina, Incomplete State-Building in Central Asia (Cham: Springer Nature, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14182-9

[6] Anna Matveeva, “Democratization, Legitimacy and Political Change in Central Asia,” International Affairs 75, no. 1 (1999): 23–44, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.00058

[7] Edward Schatz, “The Soft Authoritarian Tool Kit: Agenda-Setting Power in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan,” Nationalities Papers 44, no. 3 (2016): 493–511; Luca Anceschi, “Regime-Building, Identity-Making and Foreign Policy: Neo-Eurasianist Rhetoric in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan,” Nationalities Papers 42, no. 5 (2014): 733–749.

[8] Akchurina, Incomplete State-Building.

[9] Vedi R. Hadiz and Richard Robison, “Neo-Liberal Reforms and Illiberal Consolidations: The Indonesian Paradox,” Journal of Development Studies 41, no. 2 (2005): 220–241, https://doi.org/10.1080/0022038042000309220; Edward Aspinall, “The Irony of Success,” Journal of Democracy 21, no. 2 (2010): 20–34, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.0.0158

[10] William Case, Politics in Southeast Asia: Democracy or Less (London: Routledge, 2013); Thomas Pepinsky, “The Institutional Turn in Comparative Authoritarianism,” British Journal of Political Science 44, no. 3 (2014): 631–653, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123413000021

[11] Alexander Cooley, Great Games, Local Rules: The New Power Contest in Central Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[12] Akchurina, Incomplete State-Building.

[13] Schatz, “Soft Authoritarian Tool Kit;” Mariya Y. Omelicheva, Democracy in Central Asia: Competing Perspectives and Alternative Strategies (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2015).

[14] Paul Kubicek, “Authoritarianism in Central Asia: Curse or Cure?” Third World Quarterly 19, no. 1 (1998): 29–43, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436599814419

[15] Martha Brill Olcott, Central Asia’s New States: Independence, Foreign Policy, and Regional Security (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Institute of Peace Press, 1996).

[16] David Lewis, The Temptations of Tyranny in Central Asia (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002).

[17] World Bank, “Worldwide Governance Indicators,” 2021, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worldwide-governance-indicators#

[18] Annette Bohr, Birgit Brauer, Nigel Gould-Davies, Nargis Kassenova, Joanna Lillis, Kate Mallinson, James Nixey, and Dosym Satpayev, Kazakhstan: Tested by Transition (Chatham House Report, November 2019), https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2019-11-27-Kazakhstan-Tested-By-Transition.pdf

[19] Alexander Gabuev and Temur Umarov, “Turmoil in Kazakhstan Heralds the End of the Nazarbayev Era,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2022/01/turmoil-in-kazakhstan-heralds-the-end-of-the-nazarbayev-era?lang=en

[20] Anthony Clive Bowyer, “Political Reform in Uzbekistan – The Governance of President Mirziyoyev,” Institute for Security and Development Policy, 2018, https://www.isdp.eu/publication/political-reform-mirziyoyevs-uzbekistan/

[21] Carnegie Politika, “A Reformer’s Conundrum: How the Uzbek Regime Undermines Its Own Stability,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/russia-eurasia/politika/2023/05/a-reformers-conundrum-how-the-uzbek-regime-undermines-its-own-stability?lang=en

[22] Edward Schatz, “The Soft Authoritarian Tool Kit: Agenda-Setting Power in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan,” Nationalities Papers 44, no. 3 (2016): 493–511; Luca Anceschi, “Regime-Building, Identity-Making and Foreign Policy: Neo-Eurasianist Rhetoric in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan,” Nationalities Papers 42, no. 5 (2014): 733–749.

[23] Erik Vollmann, Miriam Bohn, Roland Sturm, and Thomas Demmelhuber, “Decentralisation as Authoritarian Upgrading? Evidence from Jordan and Morocco,” The Journal of North African Studies 25, no. 6 (2020): 865–892, https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2020.1787837.

[24] Lewis, The Temptations of Tyranny.

[25] Anceschi, “Regime-Building, Identity-Making and Foreign Policy.”

[26] Tanja A. Börzel and Thomas Risse, “The Transformative Power of Europe: The European Union and the Diffusion of Ideas,” KFG Working Paper Series 1 (2009), https://ideas.repec.org/p/erp/kfgxxx/p0001.html

[27] Timothy King and A. G. Frank, Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America: Historical Studies of Chile and Brazil (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1968), https://doi.org/10.2307/2229500; Mark R. Kauppi and Paul R. Viotti, International Relations Theory, 5th ed. (New York: Pearson, 2019).

[28] Thomas Ambrosio, “Insulating Russia from a Color Revolution: How the Kremlin Resists Regional Democratic Trends,” Demokratizatsiya 15, no. 4 (2007): 377–394.

[29] Nadège Rolland, China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative (Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2020).

[30] Nargis Kassenova, “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization and Central Asia: Co-opting the ‘Anti-Revolutionary’ Narrative,” Central Asian Affairs 29, no. 2 (2012): 145–161.

[31] James McBride, Noah Berman, and Andrew Chatzky, “China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative,” Council on Foreign Relations, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/chinas-massive-belt-and-road-initiative; Marlene Laruelle, ed., China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Its Impact in Central Asia (Washington, D.C.: George Washington University, Central Asia Program, 2018), https://centralasiaprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/OBOR_CAP_2018.pdf.

[32] Akanksha Meena, “China’s Growing Role in Central Asia,” E-International Relations, February 16, 2025, https://www.e-ir.info/2025/02/16/chinas-growing-role-in-central-asia/

[33] Temur Umarov and Nargis Kassenova, “China and Russia’s Overlapping Interests in Central Asia,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, February 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2024/02/china-and-russias-overlapping-interests-in-central-asia?lang=en

[34] Carol Saivetz, “Russia in the Caucasus and Central Asia after the Invasion of Ukraine,” MIT Center for International Studies, 2023, https://cis.mit.edu/publications/analysis-opinion/2023/russia-caucasus-and-central-asia-after-invasion-ukraine

[35] Neliana Rodean, “La Regionalizzazione Nei Paesi Dell’Europa Centro-Orientale Dopo L’allargamento,” Regional Studies and Local Development (2020), https://doi.org/10.14658/pupj-rsld-2020-1-6.

[36] Ibid.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect the opinions of the editors or the journal.